1 in 2 primary-aged kids have strong connections to nature, but this drops off in teenage years. Here's how to reverse the trend

- Written by Ryan Keith, PhD Candidate, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney

Parents and researchers have long[1] suspected[2] city kids are disconnecting from nature due to technological distractions, indoor lifestyles and increased urban density. Limited access to nature during COVID-19 lockdowns has heightened[3] such fears.

In fact, “nature-deficit disorder[4]” has become a buzzword, driving concerns about children’s well-being[5] and their ability to understand[6] and care for[7] the natural world.

Yet, there’s been surprisingly little investigation to directly test whether a disconnect exists between children and nature – and if it does, how this might affect their environmental behaviours. Our recent research[8], focused on Australian children in urban areas, sought to address this knowledge gap.

We found most younger children, especially girls, reported strong connections to nature and commitment to pro-environmental behaviours. But by their teenage years, many children have fallen out of love with nature. Understanding and reversing this trend is vital to tackling climate change, species loss and other grave environmental problems.

Young people are key to addressing environmental problems.

Henry Lydecker

Young people are key to addressing environmental problems.

Henry Lydecker

What we did

Our research involved more than 1,000 students aged 8-14 years, attending 16 public schools across Sydney.

We measured the students’ connections to nature using a questionnaire which asked about their:

- enjoyment of nature

- empathy for creatures

- sense of oneness with nature

- sense of responsibility towards nature.

The survey also canvassed students’ current environmental behaviours, such as whether they recycled waste and conserved water and energy, as well as their willingness to:

- volunteer to help protect nature

- donate money to nature charities

- talk to friends and family about protecting nature.

Read more: Being in nature is good for learning, here's how to get kids off screens and outside[9]

A girl volunteers her opinion in a group discussion at Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens.

Ryan Keith

A girl volunteers her opinion in a group discussion at Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens.

Ryan Keith

What we found

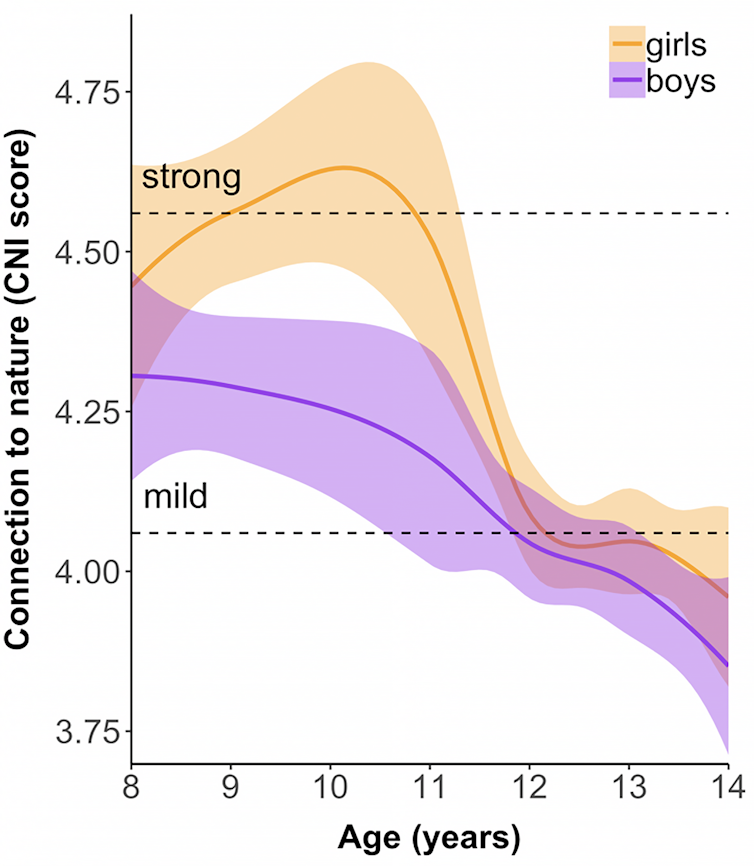

Contrary to the conventional wisdom about nature-deficit disorder, we found one in two children aged 8 to 11 felt strongly connected[10] to nature, despite living in the city. However, only one in five teens reported strong nature connections.

Children in the younger age group were also more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviours. For example, one in two were committed to saving water and energy on a daily basis, and two in three recycled each day.

Girls generally formed closer emotional connections to nature than boys did – a difference especially apparent in the final stage of primary school.

Connection to nature by age and gender. CNI = Connection to Nature Index.

Author provided

Connection to nature by age and gender. CNI = Connection to Nature Index.

Author provided

Importantly, girls differed from boys in their responses to questions about sensory stimulation. Girls particularly liked to see wildflowers, hear nature sounds and touch animals and plants. This finding echoes previous research[11] which found motivation for sensory pleasure is greater in women than men.

Girls also felt greater empathy for nonhuman animals than did boys, even after accounting for differences in sensory experience.

Children with strong nature connections were much more likely to demonstrate pro-environmental behaviours. This helps explain why girls were more willing than boys to volunteer for nature conservation.

Read more: 'Nature doesn't judge you': how young people in cities feel about the natural world[12]

Girls felt greater empathy for nonhuman animals than boys did.

www.pisquels.com

Girls felt greater empathy for nonhuman animals than boys did.

www.pisquels.com

What does all this mean?

These findings suggest parents, educators, and others[13] seeking to “reconnect[14]” youth with nature should focus on the transition between childhood and the teenage years.

Adolescence is a period of great change. Children move from primary to high school, switching peer groups[15] and struggling through puberty[16]. They gain independence[17] and must adapt to a maturing brain[18].

Relationships with nature easily fall by the wayside when teens prioritise[19] other aspects of their busy lives. In fact, evidence of the adolescent dip[20] in nature connection is emerging across different[21] cultures[22].

Educators and parents hoping to engage girls with nature might give them activities focused on sensory stimuli[23].

Girls’ greater empathy for nonhuman animals may result from societal norms[24] that socialise[25] girls to be more caring, cooperative, and empathetic[26] than boys. Boys can be encouraged to have more empathy for nonhuman animals through activities[27] focused on perspective-taking and role-playing.

Even when locked down at home, both girls and boys can cultivate empathy for animals and nourish their connections to nature by taking mindful note[28] of their surroundings. Though cities can appear to be concrete jungles, they still contain urban wildlife, parks and other green elements.

Read more: Look up! A powerful owl could be sleeping in your backyard after a night surveying kilometres of territory[29]

Children mindful of their surroundings can foster connections to nature in urban areas.

Shutterstock

Children mindful of their surroundings can foster connections to nature in urban areas.

Shutterstock

Children are the future

Recent research has demonstrated that stronger nature connections are associated with improved health and wellbeing[30] in children.

The benefits of connecting to nature should be distributed among youth in a just[31] and equitable[32] way. That means working with groups often marginalised[33] in discussions about nature, such as ethnic minorities.

Conservation[34] is increasingly reliant on young citizens forming meaningful connections with urban nature. Many environmental leaders, such as Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, are teenage girls[35].

Ensuring urban children maintain nature connections through adolescence is crucial to tackling Earth’s serious environmental problems. But it will also require more young people to confront the difficult realisation that the world’s climate is in crisis[36]. For this, we need to develop better ways to help them cope[37].

Read more: How COVID-19 has affected overnight school trips, and why this matters[38]

References

- ^ long (theconversation.com)

- ^ suspected (theconversation.com)

- ^ heightened (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ nature-deficit disorder (richardlouv.com)

- ^ children’s well-being (doi.org)

- ^ understand (theconversation.com)

- ^ care for (theconversation.com)

- ^ research (doi.org)

- ^ Being in nature is good for learning, here's how to get kids off screens and outside (theconversation.com)

- ^ strongly connected (doi.org)

- ^ previous research (doi.org)

- ^ 'Nature doesn't judge you': how young people in cities feel about the natural world (theconversation.com)

- ^ others (www.nwf.org)

- ^ reconnect (doi.org)

- ^ peer groups (doi.org)

- ^ puberty (doi.org)

- ^ independence (doi.org)

- ^ maturing brain (doi.org)

- ^ prioritise (doi.org)

- ^ adolescent dip (doi.org)

- ^ different (findingnature.org.uk)

- ^ cultures (doi.org)

- ^ sensory stimuli (doi.org)

- ^ societal norms (doi.org)

- ^ socialise (doi.org)

- ^ empathetic (doi.org)

- ^ activities (doi.org)

- ^ mindful note (www.urbanfieldnaturalist.org)

- ^ Look up! A powerful owl could be sleeping in your backyard after a night surveying kilometres of territory (theconversation.com)

- ^ improved health and wellbeing (doi.org)

- ^ just (theconversation.com)

- ^ equitable (theconversation.com)

- ^ often marginalised (theconversation.com)

- ^ Conservation (doi.org)

- ^ teenage girls (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ in crisis (theconversation.com)

- ^ cope (theconversation.com)

- ^ How COVID-19 has affected overnight school trips, and why this matters (theconversation.com)