Instagram's privacy updates for kids are positive. But plans for an under-13s app means profits still take precedence

- Written by Tama Leaver, Professor of Internet Studies, Curtin University

Facebook recently announced[1] significant changes to Instagram for users aged under 16. New accounts will be private by default, and advertisers will be limited in how they can reach young people.

The new changes are long overdue and welcome. But Facebook’s commitment to childrens’ safety is still in question as it continues to develop a separate version of Instagram for kids aged under 13.

The company received significant backlash[2] after the initial announcement in May. In fact, more than 40 US Attorneys General who usually support big tech banded together[3] to ask Facebook to stop building the under-13s version of Instagram, citing privacy and health concerns.

Read more: Is social media damaging to children and teens? We asked five experts[4]

Privacy and advertising

Online default settings matter. They set expectations for how we should behave online, and many of us will never shift away[5] from this by changing our default settings.

Adult accounts on Instagram are public by default. Facebook’s shift to making under-16 accounts private by default means these users will need to actively change their settings if they want a public profile. Existing under-16 users with public accounts will also get a prompt asking if they want to make their account private.

These changes normalise privacy and will encourage young users to focus their interactions more on their circles of friends and followers they approve. Such a change could go a long way in helping young people navigate online privacy.

Facebook has also limited the ways in which advertisers can target Instagram users under age 18 (or older in some countries). Instead of targeting specific users based on their interests gleaned via data collection, advertisers can now only broadly reach young people by focusing ads in terms of age, gender and location.

Read more: How companies learn what children secretly want[6]

This change follows recently publicised research[7] that showed Facebook was allowing advertisers to target young users with risky interests — such as smoking, vaping, alcohol, gambling and extreme weight loss — with age-inappropriate ads.

This is particularly worrying, given Facebook’s admission[8] there is “no foolproof way to stop people from misrepresenting their age” when joining Instagram or Facebook. The apps ask for date of birth during sign-up, but have no way of verifying responses. Any child who knows basic arithmetic can work out how to bypass this gateway.

Of course, Facebook’s new changes do not stop Facebook itself from collecting young users’ data. And when an Instagram user becomes a legal adult, all of their data collected up to that point will then likely inform an incredibly detailed profile which will be available to facilitate Facebook’s main business model: extremely targeted advertising.

Deploying Instagram’s top dad

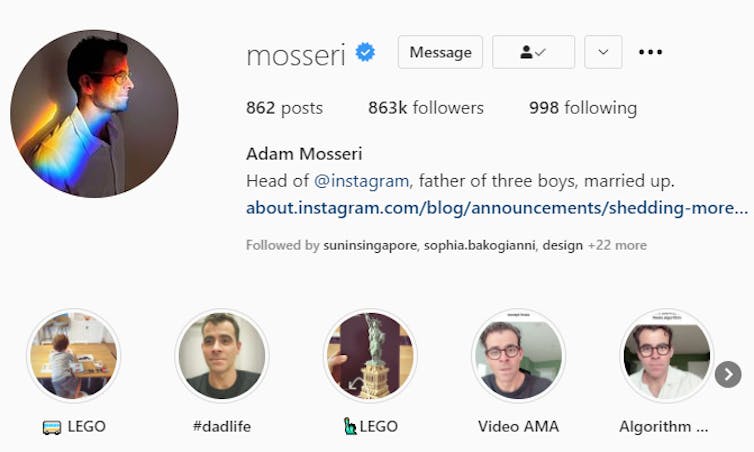

Facebook has been highly strategic in how it released news of its recent changes for young Instagram users. In contrast with Facebook’s chief executive Mark Zuckerberg, Instagram’s head Adam Mosseri[9] has turned his status as a parent into a significant element of his public persona.

Since Mosseri took over[10] after Instagram’s creators left Facebook in 2018, his profile has consistently emphasised he has three young sons, his curated Instagram stories include #dadlife and Lego, and he often signs off Q&A sessions on Instagram by mentioning he needs to spend time with his kids.

Adam Mosseri’s Instagram Profile on July 30 2021.

Instagram

Adam Mosseri’s Instagram Profile on July 30 2021.

Instagram

When Mosseri posted about the changes for under-16 Instagram users, he carefully framed the news as coming from a parent first, and the head of one of the world’s largest social platforms second. Similar to many influencers[11], Mosseri knows how to position himself as relatable and authentic.

Age verification and ‘potentially suspicious’ adults

In a paired announcement[12] on July 27, Facebook’s vice-president of youth products Pavni Diwanji announced Facebook and Instagram would be doing more to ensure under-13s could not access the services.

Diwanji said Facebook was using artificial intelligence algorithms to stop “adults that have shown potentially suspicious behavior” from being able to view posts from young people’s accounts, or the accounts themselves. But Facebook has not offered an explanation as to how a user might be found to be “suspicious”.

Diwanji notes the company is “building similar technology to find and remove accounts belonging to people under the age of 13”. But this technology isn’t being used yet.

It’s reasonable to infer Facebook probably won’t actively remove under-13s from either Instagram or Facebook until the new Instagram For Kids app is launched — ensuring those young customers aren’t lost to Facebook altogether.

Despite public backlash, Diwanji’s post confirmed Facebook is indeed still building “a new Instagram experience for tweens”. As I’ve argued in the past, an Instagram for Kids — much like Facebook’s Messenger for Kids before it[13] — would be less about providing a gated playground for children and more about getting children familiar and comfortable with Facebook’s family of apps, in the hope they’ll stay on them for life.

A Facebook spokesperson told The Conversation that a feature introduced in March prevents users registered as adults from sending direct messages to users registered as teens who are not following them.

“This feature relies on our work to predict peoples’ ages using machine learning technology, and the age people give us when they sign up,” the spokesperson said.

They said “suspicious accounts will no longer see young people in ‘Accounts Suggested for You’, and if they do find their profiles by searching for them directly, they won’t be able to follow them”.

Resources for parents and teens

For parents and teen Instagram users, the recent changes to the platform are a useful prompt to begin or to revisit conversations about privacy and safety on social media.

Instagram does provide some useful resources[14] for parents to help guide these conversations, including a bespoke Australian version of their Parent’s Guide to Instagram [15] created in partnership with ReachOut[16]. There are many other online resources, too, such as CommonSense Media’s Parents’ Ultimate Guide to Instagram[17].

Regarding Instagram for Kids, a Facebook spokesperson told The Conversation the company hoped to “create something that’s really fun and educational, with family friendly safety features”.

But the fact that this app is still planned means Facebook can’t accept the most straightforward way of keeping young children safe: keeping them off Facebook and Instagram altogether.

Read more: 'Anorexia coach': sexual predators online are targeting teens wanting to lose weight. Platforms are looking the other way[18]

References

- ^ recently announced (about.instagram.com)

- ^ significant backlash (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ banded together (www.cnbc.com)

- ^ Is social media damaging to children and teens? We asked five experts (theconversation.com)

- ^ will never shift away (doi.org)

- ^ How companies learn what children secretly want (theconversation.com)

- ^ recently publicised research (au.reset.tech)

- ^ admission (about.fb.com)

- ^ Adam Mosseri (www.instagram.com)

- ^ took over (www.amazon.com.au)

- ^ many influencers (reallifemag.com)

- ^ paired announcement (about.fb.com)

- ^ Messenger for Kids before it (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ useful resources (about.instagram.com)

- ^ Parent’s Guide to Instagram (about.instagram.com)

- ^ ReachOut (parents.au.reachout.com)

- ^ Parents’ Ultimate Guide to Instagram (www.commonsensemedia.org)

- ^ 'Anorexia coach': sexual predators online are targeting teens wanting to lose weight. Platforms are looking the other way (theconversation.com)