A controversial US book is feeding climate denial in Australia. Its central claim is true, yet irrelevant

- Written by Ian Lowe, Emeritus Professor, School of Science, Griffith University

My heart sank last week to see conservative Australian commentator Alan Jones championing a contentious book about climate science which has gained traction in the United States.

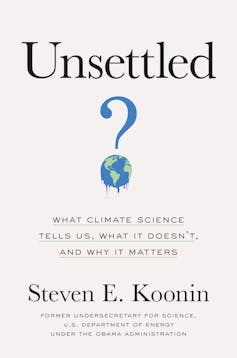

BenBella Books

The book, titled Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters, is authored by US theoretical physicist Steven Koonin. Notably, Koonin is not a climate scientist.

As the title suggests, the book’s bold central theme is that climate science is far from settled, and should not be relied on to make policy choices in areas such as energy, transport and economics.

Jones cited Koonin’s book[1] in a Daily Telegraph column last week. He decried the “nonsense” of governments in Australia and abroad aiming for net-zero carbon emissions, saying it was as though Koonin’s book “didn’t exist”.

So does the book hold up? I have been researching and writing about climate change since the 1980s. I wanted to give the book a fair reading, so I put any preconceived thoughts aside and tried to fairly weigh up Koonin’s arguments. If true, they would be very important findings.

Koonin frames his book as a brave attempt to reveal how the climate science we’ve been relying on all these years is, in fact, uncertain. But the book’s major flaw is to imply these uncertainties are news to climate scientists.

This is patently untrue. Science is never settled. But there is enough confidence in the science to justify significant climate action.

BenBella Books

The book, titled Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters, is authored by US theoretical physicist Steven Koonin. Notably, Koonin is not a climate scientist.

As the title suggests, the book’s bold central theme is that climate science is far from settled, and should not be relied on to make policy choices in areas such as energy, transport and economics.

Jones cited Koonin’s book[1] in a Daily Telegraph column last week. He decried the “nonsense” of governments in Australia and abroad aiming for net-zero carbon emissions, saying it was as though Koonin’s book “didn’t exist”.

So does the book hold up? I have been researching and writing about climate change since the 1980s. I wanted to give the book a fair reading, so I put any preconceived thoughts aside and tried to fairly weigh up Koonin’s arguments. If true, they would be very important findings.

Koonin frames his book as a brave attempt to reveal how the climate science we’ve been relying on all these years is, in fact, uncertain. But the book’s major flaw is to imply these uncertainties are news to climate scientists.

This is patently untrue. Science is never settled. But there is enough confidence in the science to justify significant climate action.

Scientific uncertainty does not justify climate inaction.

Shutterstock

Uncertainty is par for the course

Koonin opens the book by saying he accepts that Earth is warming, and humans are contributing to this. But he muddies the waters with passages such as the following:

Past variations of surface temperature and ocean heat content do not at all disprove that the (approximately 1℃) rise in the global average surface temperature anomaly since 1880 is due to humans, but they do show that there are powerful natural forces driving the climate as well.

In other words, Koonin says, the real question is “to what extent this warming is being caused by humans”.

Scientific uncertainty does not justify climate inaction.

Shutterstock

Uncertainty is par for the course

Koonin opens the book by saying he accepts that Earth is warming, and humans are contributing to this. But he muddies the waters with passages such as the following:

Past variations of surface temperature and ocean heat content do not at all disprove that the (approximately 1℃) rise in the global average surface temperature anomaly since 1880 is due to humans, but they do show that there are powerful natural forces driving the climate as well.

In other words, Koonin says, the real question is “to what extent this warming is being caused by humans”.

The book’s author, Steven Koonin, is not a climate scientist.

Kelly Kollar

No rational person could deny that natural forces drive the climate. The climate record shows significant[2] climate changes long before humans existed; clearly we’re not responsible for the planet being much warmer many millions of years ago.

However the five assessment reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[3] have expressed steadily increasing confidence that humans are the dominant cause of global warming this century.

Koonin attacks former US secretary of state and now Biden climate envoy, John Kerry, who once said of climate change “the science is unequivocal”.

It is true to say climate science is somewhat uncertain. Science is always a work in progress. Scientific integrity demands a willingness to look carefully at new data and theories to see if they require us to revise what we thought we knew.

But Koonin is wrong to imply scientists are somehow unaware of, or deny, this uncertainty. To the contrary, I have heard decision-makers express exasperation when we scientists seek to qualify our advice on the basis that our knowledge is limited.

Every reputable climate scientist I know is always willing to look at new data. But policy-makers must make decisions based on the current scientific understanding.

Koonin states, accurately, that few in the general public receive scientific information directly from research papers. Most people receive climate change information after it’s been filtered by governments and the media – which, in Koonin’s mind, often overstate the seriousness of climate change.

However Koonin fails to note the opposite forces at play – governments and media organisations, such as the Murdoch press[4] in Australia and Fox News[5] in the US, which systematically misreport climate science and underestimate the climate threat.

Read more:

Climate explained: why is the Arctic warming faster than other parts of the world?[6]

The book’s author, Steven Koonin, is not a climate scientist.

Kelly Kollar

No rational person could deny that natural forces drive the climate. The climate record shows significant[2] climate changes long before humans existed; clearly we’re not responsible for the planet being much warmer many millions of years ago.

However the five assessment reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[3] have expressed steadily increasing confidence that humans are the dominant cause of global warming this century.

Koonin attacks former US secretary of state and now Biden climate envoy, John Kerry, who once said of climate change “the science is unequivocal”.

It is true to say climate science is somewhat uncertain. Science is always a work in progress. Scientific integrity demands a willingness to look carefully at new data and theories to see if they require us to revise what we thought we knew.

But Koonin is wrong to imply scientists are somehow unaware of, or deny, this uncertainty. To the contrary, I have heard decision-makers express exasperation when we scientists seek to qualify our advice on the basis that our knowledge is limited.

Every reputable climate scientist I know is always willing to look at new data. But policy-makers must make decisions based on the current scientific understanding.

Koonin states, accurately, that few in the general public receive scientific information directly from research papers. Most people receive climate change information after it’s been filtered by governments and the media – which, in Koonin’s mind, often overstate the seriousness of climate change.

However Koonin fails to note the opposite forces at play – governments and media organisations, such as the Murdoch press[4] in Australia and Fox News[5] in the US, which systematically misreport climate science and underestimate the climate threat.

Read more:

Climate explained: why is the Arctic warming faster than other parts of the world?[6]

Humans are the dominant cause of global warming this century.

Shutterstock

Ignorance is not bliss

Koonin concludes by questioning the wisdom of reaching net-zero emissions in the second half of this century - a central goal of the Paris Agreement. He argues that when one balances the cost and efficacy of slashing emissions “against the certainties and uncertainties in climate science”, the net-zero goal looks implausible and unfeasible.

This is effectively an assertion that ignorance is bliss: because we don’t have perfect understanding that allows us to make exact projections about the future climate, we should not take serious action to reduce emissions.

Koonin proposes a different response: for society to adapt to a changing climate, and embrace “geoengineering” technology to artificially control[7] Earth’s climate.

Both adaptation and geoengineering[8] have their place in the climate response. But neither are sufficient[9] substitutes for dramatically cutting carbon emissions.

Read more:

Solar geoengineering is worth studying but not a substitute for cutting emissions, study finds[10]

Humans are the dominant cause of global warming this century.

Shutterstock

Ignorance is not bliss

Koonin concludes by questioning the wisdom of reaching net-zero emissions in the second half of this century - a central goal of the Paris Agreement. He argues that when one balances the cost and efficacy of slashing emissions “against the certainties and uncertainties in climate science”, the net-zero goal looks implausible and unfeasible.

This is effectively an assertion that ignorance is bliss: because we don’t have perfect understanding that allows us to make exact projections about the future climate, we should not take serious action to reduce emissions.

Koonin proposes a different response: for society to adapt to a changing climate, and embrace “geoengineering” technology to artificially control[7] Earth’s climate.

Both adaptation and geoengineering[8] have their place in the climate response. But neither are sufficient[9] substitutes for dramatically cutting carbon emissions.

Read more:

Solar geoengineering is worth studying but not a substitute for cutting emissions, study finds[10]

The world must urgently reduce emissions.

Shutterstock

Proceed with caution

Under the Hawke government, science minister Barry Jones was one of the first public figures[11] in Australia to sound warnings about climate change.

Jones and I both appeared on a panel at a landmark climate conference[12] in 1987. I recall Jones, when asked how decision-makers should respond, said we should consider the consequences of both acting and not acting.

If policymakers acted on inaccurate climate science, Jones argued, the worst that would happen is our energy would be cleaner – albeit, at that time, more expensive. But if the science was right and we ignored it, the consequences could be catastrophic.

Jones was essentially describing the precautionary principle, which is contained in a number of international treaties including the UN’s Rio Declaration, which states[13]:

Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.

The principle demands we act to avoid disastrous outcomes, even if the science is uncertain. Because the uncertainty works both ways: things might get worse than we expect, rather than better.

The fundamental point of Koonin’s book is true, but irrelevant. The science is not settled – but we know enough to act decisively.

Read more:

Even without new fossil fuel projects, global warming will still exceed 1.5℃. But renewables might make it possible[14]

The world must urgently reduce emissions.

Shutterstock

Proceed with caution

Under the Hawke government, science minister Barry Jones was one of the first public figures[11] in Australia to sound warnings about climate change.

Jones and I both appeared on a panel at a landmark climate conference[12] in 1987. I recall Jones, when asked how decision-makers should respond, said we should consider the consequences of both acting and not acting.

If policymakers acted on inaccurate climate science, Jones argued, the worst that would happen is our energy would be cleaner – albeit, at that time, more expensive. But if the science was right and we ignored it, the consequences could be catastrophic.

Jones was essentially describing the precautionary principle, which is contained in a number of international treaties including the UN’s Rio Declaration, which states[13]:

Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.

The principle demands we act to avoid disastrous outcomes, even if the science is uncertain. Because the uncertainty works both ways: things might get worse than we expect, rather than better.

The fundamental point of Koonin’s book is true, but irrelevant. The science is not settled – but we know enough to act decisively.

Read more:

Even without new fossil fuel projects, global warming will still exceed 1.5℃. But renewables might make it possible[14]

References

- ^ cited Koonin’s book (www.dailytelegraph.com.au)

- ^ significant (theconversation.com)

- ^ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (www.ipcc.ch)

- ^ Murdoch press (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ Fox News (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ Climate explained: why is the Arctic warming faster than other parts of the world? (theconversation.com)

- ^ artificially control (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ geoengineering (e360.yale.edu)

- ^ sufficient (www.nap.edu)

- ^ Solar geoengineering is worth studying but not a substitute for cutting emissions, study finds (theconversation.com)

- ^ first public figures (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ climate conference (www.cawcr.gov.au)

- ^ which states (www.jus.uio.no)

- ^ Even without new fossil fuel projects, global warming will still exceed 1.5℃. But renewables might make it possible (theconversation.com)