What happens when you pay Year 7 students to do better on NAPLAN? We found out

- Written by Jayanta Sarkar, Associate professor of economics, Queensland University of Technology

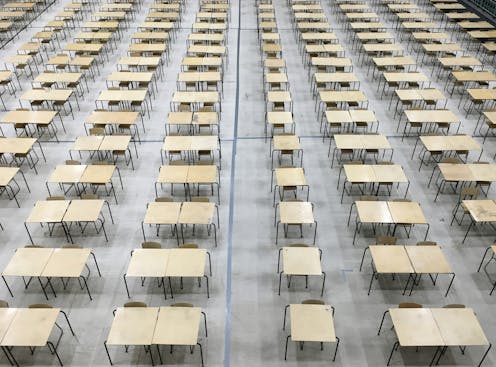

Next month, we are expecting the results from the annual NAPLAN tests, which students in years 3, 5, 7 and 9 sat earlier this year.

Each year, the tests are widely promoted as a marker of student progress and are used to inform decisions about what is needed in Australian schools.

There has been increasing concern about students’ performance in these tests. For example, last year[1] only two-thirds of students met the national standards, with headlines of “failed NAPLAN expectations[2]”.

But what if students weren’t trying as hard as they could in these tests? Our research suggests that may be the case.

In our new study[3], Year 7 students were given small financial rewards if they reached personalised goals in their NAPLAN tests. We found this improved their results.

Who did we study?

Rewarding students to do better on tests is not a new concept[4] and is unsurprisingly controversial[5] in education policy.

But we wanted to explore this to better understand students’ motivation and effort while taking a test.

In our study, we used data on real students doing NAPLAN tests. We selected this test because it is a national test where performance improvement is vitally important for schools, yet the stakes are low for students. NAPLAN results do not have an impact on their final grades.

We looked at three groups of Year 7 students, in 2016, 2017 and 2018. The number of tests observed for each year was 537, 637 and 730, respectively.

The students were at a coeducational public high school in South East Queensland and mostly came from socio-educationally disadvantaged[6] backgrounds.

How were the students rewarded?

In each year, students sat four tests. Before each test, students were given a personalised target score, based on their Year 5 NAPLAN results. There was then a different approach for each test:

in the conventions of language (spelling, grammar and punctuation) test, students were given no incentive to reach their target score. This provided the benchmark for comparison in our study.

in the writing test, students were given a “fixed” incentive. This was a canteen voucher worth A$20 if they reached their target score.

in the reading and numeracy tests, students were either given a “proportional” incentive or a “social” incentive.

For the proportional incentive, they got a $4 voucher for every percentage point over and above their target score, up to a maximum of $20. For the social incentive, they were organised into groups of about 25. They would each get a $20 voucher if their group had the highest average gain in scores between Year 5 and Year 7 of all the groups.

To make sure any improvement in test scores could only occur through increased effort (and not increased preparation), the incentives were announced by the school principal in a prerecorded message, just minutes before the start of each test.

The rewards were handed out by the school 12 weeks after the exams, once results were released.

We found scores improved with rewards

Our research found scores improved when students were offered a reward, particularly for tests done in 2017 and 2018.

When compared with the gains in conventions of language test (where students were not given any incentive), the average scores improved by as much as 1.37% in writing, 0.81% in reading and 0.28% in numeracy.

While these may not seem like huge overall gains, our analysis showed the rewards led to gains that went above and beyond the gains seen at similar schools (that didn’t offer incentives). Our results are backed by strong statistical validity[9] (or precision), which provides a very high level of confidence these gains were due to the reward.

What reward worked best?

We saw the largest impact when students had a fixed incentive, followed by the proportional incentive and then the group incentive.

This is perhaps not surprising, as the fixed incentive paid the highest reward for an individual’s effort. But it is interesting the biggest gain was in writing, given this is an area where Australian students’ performance has dropped over the past decade[12], with a “pronounced” drop in high school.

It is also surprising that students’ individual efforts still increased when the reward depended on other students’ performances. All the test takers were new to high school and would not have had long to establish the kind of group cohesion[13] that typically makes group rewards effective.

Another surprise is the fact the rewards had an impact even when they came with a delay of 12 weeks. Previous research[14] suggests rewards would need to be given to students immediately or soon after their efforts in order to have an effect.

What does this mean?

Our findings suggest students can be motivated to increase their test-taking effort in multiple subjects, by small monetary incentives.

This is not to say we should be paying students for their test performances more broadly. But it does suggest poor performance in low-stakes tests may reflect students’ efforts rather than their ability or their learning.

These findings raise questions about the extent to which we use tests such as NAPLAN – and whether parents, teachers and policy-makers need to look further if they are making important decisions based on these test results.

References

- ^ last year (theconversation.com)

- ^ failed NAPLAN expectations (www.skynews.com.au)

- ^ new study (doi.org)

- ^ not a new concept (doi.org)

- ^ controversial (doi.org)

- ^ socio-educationally disadvantaged (docs.acara.edu.au)

- ^ Nik/Unsplash (unsplash.com)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ statistical validity (sites.education.miami.edu)

- ^ Ben Mullins/Unsplash (unsplash.com)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ dropped over the past decade (www.edresearch.edu.au)

- ^ group cohesion (www.le.ac.uk)

- ^ research (doi.org)