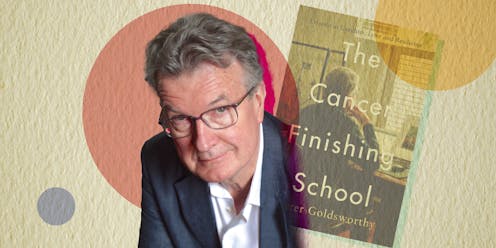

In his entertaining cancer memoir, Peter Goldsworthy explores the ‘necessary narcissism’ of illness

- Written by David McCooey, Professor of Writing and Literature, Deakin University

Illness memoir is based on a tension between the general and the particular. The writer presents (to use a medical term) as both representing all sufferers of a particular malady – in this case, myeloma – and a unique individual experiencing a specific, unrepeatable event. Peter Goldsworthy, who is both a GP and a prize-winning writer, is better equipped than most to engage with this tension.

Indeed, one of the reasons The Cancer Finishing School[1] is so exciting (if I can use such a word in this context) is because it so effectively deals with this. It ties together the experiential and the abstract, the intellectual and the embodied, and the everyday and the extraordinary (not to mention other tensions more specific to cancer, such as between rationalism and magical thinking).

Review – The Cancer Finishing School by Peter Goldsworthy (Penguin)

Myeloma is a type of blood cancer[2] that develops in the bone marrow and is both “an incurable disease” and a “good cancer to get”.

His memoir follows a simple narrative arc, familiar to illness memoirs (or “autopathography[3]”) : diagnosis (accidentally via a scan of a problematic knee); treatment (with chemotherapy); hospitalisation (for a stem-cell transplant); and the return home (for recuperation).

And yet, Goldsworthy, the good writer-doctor that he is, makes this familiar journey utterly compelling. The reasons for this are, to use a term favoured by doctors, multifactorial[4].

At one level, Goldsworthy’s account is gripping because the simple facts are inherently interesting. Stem-cell transplant is an extraordinary medical procedure – half science-fiction, half medieval trial by ordeal – involving liquid mustard gas and the killing off of the patient’s bone marrow. This process, Goldsworthy notes, has the alarming mortality rate of 10% after 200 days.

The chemotherapy is also, perhaps surprisingly, fascinating. In this instance, it employs a steroid hormone called dexamethasone[5] to counter the side effects of the chemotherapeutic agents. Dexamethasone produces periods of intense creativity and activity in Goldsworthy. Recreating “Dex bliss” is the source of much febrile inventiveness in the first third of The Cancer Finishing School.

Read more: Living with complex illness and surviving to tell about it: Anna Spargo-Ryan's chronic optimism[6]

But “good material” is not in itself enough. Goldsworthy puts a lot of effort into representing what we might call the phenomenological intensity of not just the “dex” mania, but the entire “journey” of cancer.

Faced with the prospect of death, Goldsworthy recounts a time of intense living, and he gives a powerful sense of what that experience was like bodily and emotionally (a distinction that dexamethasone profoundly calls into question).