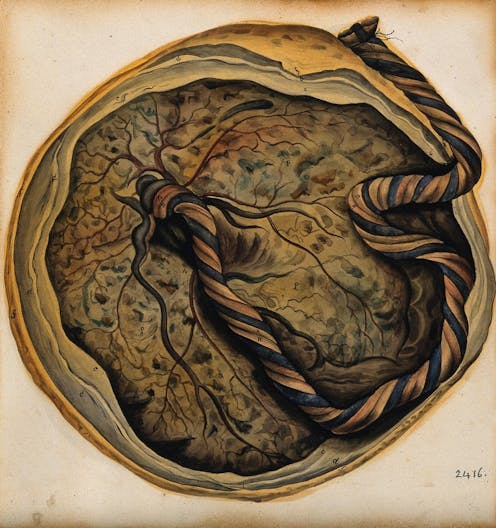

it reminded him of a cake

- Written by Paige Donaghy, Early career researcher, The University of Queensland

Ever wondered where the placenta got its name?

In Italy in the 1500s, the anatomist Matteo Realdo Colombo coined this term to describe the large fleshy organ of pregnancy. Colombo chose placenta because it resembled another big, round object seen in daily life: a cake.

In the premodern world, there existed a variety of words and concepts used to understand the placenta.

In my research[1], I try to uncover the cultural significance of the placenta and afterbirth in premodern Europe (1500–1800) to help us better understand the social and medical history of this important organ.

Read more: Explainer: what is placenta?[2]

Afterbirths and secundines

Before the anatomical term placenta appeared, men and women in medieval Europe used the terms “afterbirth” (nachgeburt in German, arrière-faix in French) and “the second” (secundina in Italian, secondine in English).

These terms captured the fact that placental expulsion was the “second” part of a childbirth, necessary to end the birth.

From the medieval to late early modern period, childbirth was very much the preserve of women midwives, family members and neighbours. Much of their knowledge about the placenta was transmitted orally (women were generally not literate, unless elite) yet some of this knowledge survives in texts[4].

Male physicians recorded women’s knowledge about childbirth to demonstrate they could access “secret” knowledge about women’s bodies. This boosted their reputation among other male physicians, and gave credibility to their expertise over women’s health and childbirth.

One example of this is the 12th century medical compendium, The Trotula[5], one of the most influential works on women’s medicine in Europe from its publication until well into the 1500s.

The text, a compilation of different medical treatises, was supposedly authored by the first female physician and professor, Trota, in Salerno, Italy.

Although modern scholars suggest that some of the text’s authors were certainly male, historian Monica Green[7] argues that part of the work was likely shaped by a female midwife or healer, possibly called Trota.

At this time, there were many female healers in Salerno, and it was typically only women who had access to women’s births and bodies.

Examining The Trotula allows us to see earlier cultural and medical ideas about the placenta. The author describes how, during birth:

The foetus is expelled from its bed, that is to say the afterbirth, by the force of Nature.

The afterbirth and foetus were understood as having a close, companion-like relationship; the placenta was a “bed” for the foetus during pregnancy, providing support and comfort.

We can also see how the afterbirth might be used following pregnancy and birth. Trota writes:

If [the mother] has been badly torn in birth and afterward for fear of death does not wish to conceive any more, let her put into the afterbirth as many grains of caper spurge or barley as the number of years she wishes to remain barren.

The post-birth use of the placenta in remedies was common in Europe. The afterbirth was perceived as having “sympathetic” healing qualities relating to future fertility and the health of the infant.

Anatomy and the afterbirth: new terms

Women’s ideas about placental remedies were often ridiculed by university-educated male anatomists, who labelled these practices “superstitious”. Yet, many did respect women’s knowledge as experts in childbirth.

When Italian anatomist Matteo Realdo Colombo coined the term “placenta” in the 16th century, he used a term directly related to women’s worlds: cooking. Colombo was professor of anatomy at the University of Padua, a hub for anatomical learning[9] in Europe at the time.

Colombo described the shape and function of the human placenta in his anatomical treatise, De Re Anatomica (On Things Anatomical, 1559).

In this book, Colombo introduced the term “placenta” to distinguish it from other anatomical terms, as well as midwifery terms like “secundina”.

“Placenta” referred to a wide, flat cake, cooked in a pan with layers of cheese and honey, dating as far back[10] as Ancient Rome.

Colombo chose this term to describe the large, flat organ, “circular” like a placenta cake, and of a similar size.

In choosing the term placenta, he also associated the organ with ideas about women’s worlds, of cooking and childbirth; the placenta, like the Italian cake, provided nourishment and comfort. This idea connected with earlier ones like the Trotula, which suggested the afterbirth was the foetus’ bed.

The placenta today

Exploring the history of ideas about the placenta and afterbirth offer us insights into how people have valued this important organ.

This can tell us about the development of scientific knowledge, such as the emergence of the word placenta, providing context for urgent placental science[11] being undertaken today. History can help us determine how and why in different times and cultures, science has or has not prioritised placental research.

Histories of the placenta also help provide context for current cultural attitudes to and practices around the afterbirth, such as eating the placenta[12] and turning the placenta into memorabilia, jewellery or art[13].

By studying past knowledge about the placenta, we can see the echoes of attitudes to this organ in our modern science and culture.

Our bodies are not static. They are deeply shaped by the prevailing medical and cultural perceptions of our times.

Read more: No, you shouldn't eat your placenta, here's why[14]

References

- ^ my research (www.journals.uchicago.edu)

- ^ Explainer: what is placenta? (theconversation.com)

- ^ Wellcome Library (wellcomecollection.org)

- ^ survives in texts (blogs.bl.uk)

- ^ The Trotula (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Wikimedia Commons (commons.wikimedia.org)

- ^ historian Monica Green (www.youtube.com)

- ^ Wikimedia Commons (commons.wikimedia.org)

- ^ anatomical learning (www.unipd.it)

- ^ as far back (www.google.com.au)

- ^ urgent placental science (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ eating the placenta (theconversation.com)

- ^ memorabilia, jewellery or art (midwifebalance.com.au)

- ^ No, you shouldn't eat your placenta, here's why (theconversation.com)