Efforts to find safe housing for homeless youth have gone backwards. Here's what the new national plan must do differently

- Written by David MacKenzie, Associate Professor, University of South Australia

What needs to change to greatly reduce youth homelessness in Australia? Now is the time to find answers to this question, and not just because it’s National Homelessness Week[1].

The federal government is developing a National Housing and Homelessness Plan[2] and says[3] public consultations will begin soon. In recent years, there have been two parliamentary inquiries into homelessness in Victoria[4] and across Australia[5]. Then came a Productivity Commission review[6] of the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement[7], which expired on June 30 this year.

More than a decade ago, the Rudd government made homelessness a national priority. A 2008 white paper, The Road Home[8], advanced three key strategies:

- “turning off the tap” – early intervention and prevention

- “improving and expanding services” – the existing service system

- “breaking the cycle” – supported housing to prevent homelessness reoccurring.

Yet today more people need help[9] because of homelessness than 15 years ago. The ambitious agenda of 2008 has not been fulfilled[10].

The forthcoming plan might just be a second chance for Australia to get it right.

Read more: Yes, we see you. Why a national plan for homelessness must make thousands of children on their own a priority[11]

Homelessness is more than ‘sleeping rough’

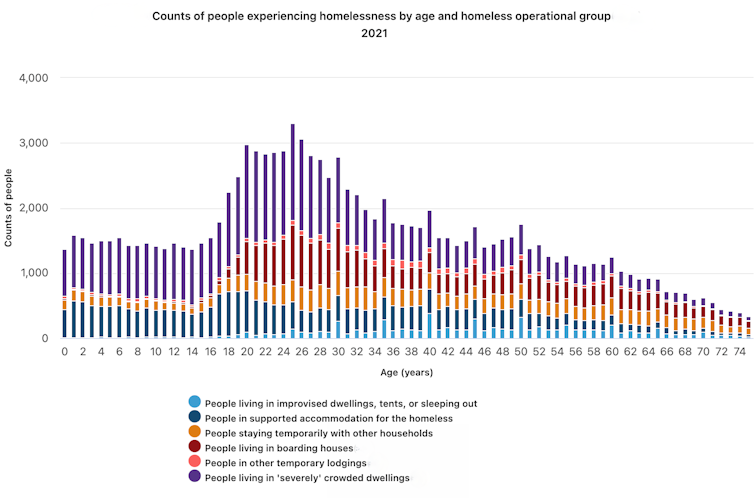

Homelessness conjures images of someone sleeping in a doorway, alley or city park. “Rough sleeping” is, after all, the visible homelessness that people see. But there are other forms of homelessness that are more hidden.

Some vocal advocates[12] seek to model the Australian homelessness response on that of the United States. In the US, nearly 600,000 people[13] are sleeping rough or in shelters. The rate of homelessness is at least ten times the rate in Australia[14].

A problem in the US is that homelessness is very narrowly defined. Fortunately, in Australia, homelessness has been understood and defined more broadly[15] as not having a secure and safe home. So the good news is the new homelessness plan is unlikely to make the mistake of adopting the narrow US focus on rough sleeping.