In the 1800s, colonisers attempted to listen to First Nations people. It didn't stop the massacres

- Written by Stephen Gapps, Historian and Conjoint Lecturer, University of Newcastle

Note of warning: This article refers to deceased Aboriginal people, their words, names and images. Words attributed to them and images in the article are already in the public domain. Also, historical language is used in this article that may cause offence.

As we head toward the referendum on the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to Parliament later this year, it is worth considering the long history of how governments have tried and failed to authentically listen to First Nations people.

And not just post-federation governments. During Australia’s colonial period in the 19th century, the office of the Protector of Aborigines was established in an effort to hear to the “wants, wishes and grievances” of Aboriginal people, as the secretary for the colonies, Lord Glenelg[1], put it in 1838.

However, this office not only failed to genuinely listen to First Nations peoples, it led to policies that actually underpinned the erasure of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from the Australian Constitution of 1901.

Spotlight on the treatment of Indigenous people

During the 1830s, slave rebellions[2] in Britain’s colonies and a growing humanitarian movement in the UK pushed the government to abolish slavery. The spotlight was then turned on the treatment of Indigenous peoples, both within and on the edges of the rapidly expanding British Empire.

In 1836, the British government established a Select Committee of the House of Commons on Aborigines[3] to hear testimony from church leaders, missionaries and colonial officials about the situation of Aboriginal people in the Australian colonies.

The hearings focused particular attention on the conduct of militia forces in the so-called Black War[4] in Tasmania, where roving parties of white men hunted down and killed Palawa people and massacres were seen as part and parcel of occupying Aboriginal lands.

In January 1838, Glenelg wrote to the governor[5] of New South Wales, Sir George Gipps, that the British government

[had] directed their anxious attention to the adoption of some plan for the better protection and civilisation of the native tribes.

Glenelg told Gipps that as part of the scheme, the British government had decided to “appoint a small number of persons qualified to fill the office of Protector of Aborigines”. The chief protector, a non-Indigenous person, was to be aided by four assistant protectors and to “fix his principal station at Port Phillip” (later to become Melbourne), only recently occupied by the British.

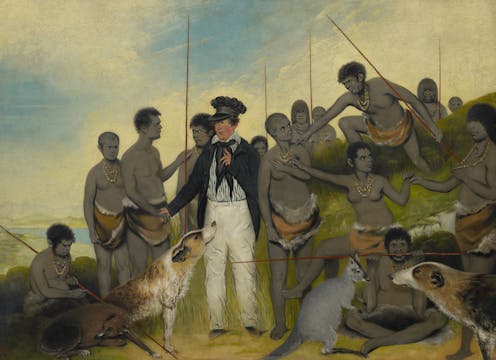

According to Glenelg, George Augustus Robinson[6] was bestowed with the office of chief protector as he had

shewn [sic] himself to be eminently qualified by his charge of the Aboriginal Establishment at Flinders Island.

Robinson’s so-called “Friendly Mission[7]” - a series of journeys around Tasmania in the early 1830s to convince Palawa of Governor George Arthur’s humane intentions - was lauded by Gipps as a success, as it had peacefully convinced some people to move to a reserve at Flinders Island. Historians now consider this mission to be nothing more than ethnic cleansing[8].

For Glenelg, appointing Robinson to the new position of chief protector appeared to be the only plan available that did not involve military or police, or armed settlers dispensing their own “justice”.

An aim to convey ‘wants, wishes or grievances’

The plan for establishing Aboriginal protectorates followed Robinson’s Friendly Mission model in Tasmania.

Protectors were to “watch over the rights and interests of the natives” and protect them from “acts of cruelty, of oppression or injustice”. The protector was also to be a kind of conduit to express the “wants, wishes or grievances” of Aboriginal peoples to the colonial governments. For this purpose, each protector was commissioned as a magistrate.

Protectors were encouraged to learn the “language of the natives” and “obtain accurate information” on the “number of the natives within his district”.

On paper at least, the “plan for the better protection and civilisation of the native tribes” seemed a remarkable step forward from previous years. Indeed, there was no plan prior to this that attempted to deal with the situation in Aboriginal lands beyond the official boundaries of the colonies – boundaries that were being increasingly crossed by hundreds of squatters and stockmen, and tens of thousands of cattle and sheep.

The establishment of the role of protectors, who would live among Aboriginal people and learn their languages, was arguably an early attempt at a conduit for an Aboriginal voice to government.

Read more: 90 years ago, Yorta Yorta leader William Cooper petitioned the king for Aboriginal representation in parliament[9]

A failure from the beginning

But the scheme did not stop the conflicts and massacres. Shortly after the commission’s report appeared in print in Australia, dozens of Gamilaraay people were killed at Waterloo Creek[10] and Myall Creek[11] in northern inland New South Wales in January and June 1838.

The scheme also did little to stop the resistance warfare that broke out across the entire length of the frontier in the late 1830s and early 1840s – a counteroffensive that has been described by some contemporary observers as a “general uprising”.

The protectorates scheme was also bound up in the supposed superiority of the colonisers’ race and Christian religion. The ultimate goal was for Aboriginal people to become “civilised” and Christian – just like white people apparently were. It was a paternalistic concept that ultimately turned humanitarian ideals into an even more violent and coercive colonial system.

The protectors, as they had been directed to, could report to the government the “grievances” of Aboriginal people. These were often found to be, as one observer at the time[12] wrote,

[an] explosion of long-pent feelings of revenge and hatred towards the whites, resulting from a long course of violence and injustice.

The attempt by the colonial authorities to understand the “wants, wishes and grievances” of Aboriginal people, however, failed in its mission to actually protect people. The system was abandoned in 1849.

From the 1860s, the various colonial governments developed even more coercive policies of “protection”, which controlled peoples’ lives and corralled them into missions and reserves, so their lands and children could be taken from them.

Read more: Capturing the lived history of the Aborigines Protection Board while we still can[13]

How this history feeds into failed policies today

The Protector of Aborigines office was an important historical moment that embedded this idea of government control over First Nations’ people’s lives into the social and political fabric of this nation. These supposedly moral standards around “protection” and “civilisation” ultimately forced Indigenous people to become less Indigenous.

These beliefs continue to permeate our government today through failed paternalistic policies such as Closing the Gap. Such racialised policies draw on Australia’s history of containment of Aboriginal land and the ongoing colonial violence of “protection”.

Because of this, we have yet to generate new possibilities of truly meaningful dialogue.

The long struggle for rights and recognition by Aboriginal people has been punctuated by (all too few) moments of support by non-Aboriginal people. As the referendum for the Voice approaches, another such moment beckons. Will this be history repeating itself?

References

- ^ Lord Glenelg (adb.anu.edu.au)

- ^ slave rebellions (www.blackpast.org)

- ^ Select Committee of the House of Commons on Aborigines (wellcomecollection.org)

- ^ Black War (theconversation.com)

- ^ wrote to the governor (nla.gov.au)

- ^ George Augustus Robinson (adb.anu.edu.au)

- ^ Friendly Mission (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ ethnic cleansing (www.academia.edu)

- ^ 90 years ago, Yorta Yorta leader William Cooper petitioned the king for Aboriginal representation in parliament (theconversation.com)

- ^ Waterloo Creek (c21ch.newcastle.edu.au)

- ^ Myall Creek (myallcreek.org)

- ^ one observer at the time (adb.anu.edu.au)

- ^ Capturing the lived history of the Aborigines Protection Board while we still can (theconversation.com)