Hate crimes against Muslims spiked after the mosque attacks, and Ardern promises to make such abuse illegal

- Written by The Conversation

What is the relationship between hate crimes and terrorism?

Could we have predicted the terror attacks at Masjid Al Noor and the Linwood Islamic Centre on March 15 last year if we had been able to identify a rising number of verbal and physical attacks against Muslims in the preceding months and years?

In New Zealand, we currently can’t answer these questions. Authorities don’t maintain a register of hate crimes (defined as verbal and physical assaults motivated by hatred of the victim’s group identity). Nor does our legal system recognise hate crime as a separate offence.

Amending the Human Rights Act 1993[1] has now become an election issue, with Prime Minister and Labour leader Jacinda Ardern saying it is her party’s intention to revise the law[2] to make it illegal to abuse or threaten people because of their religious identity.

This would add to the provisions against intimidation along ethnic, national and racial lines already covered by the law[3].

But ACT Party leader David Seymour has said any such move would threaten New Zealanders’ freedom of expression. He called proposed hate speech laws “divisive and dangerous[4]”.

A preliminary register of hate crimes

The lack of data means we have no way of knowing if hate crimes against minorities are becoming more common. And we can’t tell if they are more prevalent in certain regions of New Zealand or if particular groups are targeted more than others.

We also can’t determine the relationship between hate crimes and major events such as the Christchurch terrorist attacks or COVID-19. This means we can’t predict when and where identity-related crime might take place, or act to prevent it.

Read more: Far-right extremists still threaten New Zealand, a year on from the Christchurch attacks[5]

To address this gap and begin to answer these questions, we, along with students from the University of Auckland, have searched media reports for any verbal or physical assaults motivated by the perpetrator’s hatred of the victim’s ethnic or religious identity. Hate crimes also include targeting people because of their gender or sexual identity, but we have focused on ethnicity and religion.

This is far from the most ideal way to collect data, but it is a first step in gaining a more systematic view of identity crime in New Zealand. The result is a preliminary dataset of hate crime incidents in this country between 2013 and August 2020.

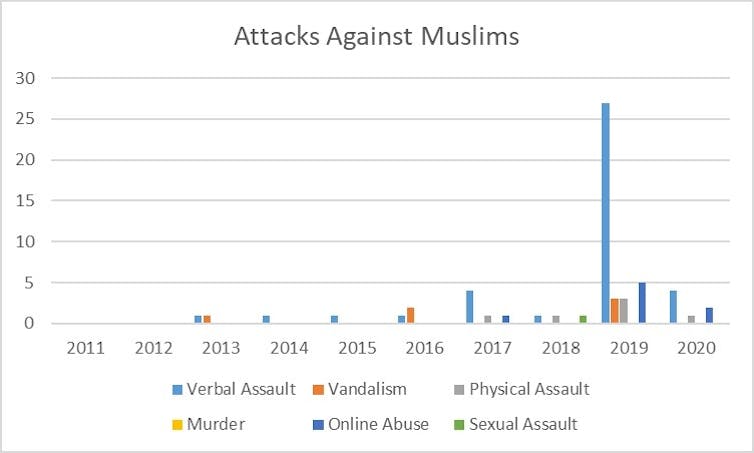

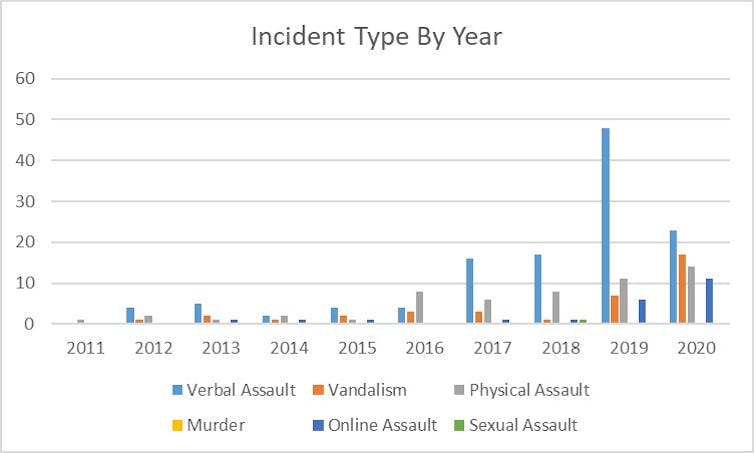

Our data demonstrate a steady if slight increase in hate crimes until 2019 when the number of incidents rose sharply. Here, we focus on the relationship between the Christchurch terrorist attacks and verbal and physical hate crimes against Muslims.

Author provided Academic studies show hate crimes sometimes act as a “red flag[6]” of an impending terrorist attack. More commonly, terrorist attacks can spur a rise in hate crimes[7], as members of the group targeted by terrorism exact revenge against the terrorists’ ethnic or religious community. After the September 11 twin-tower attacks in the United States in 2001, hate crimes against Muslims and Arabs increased 1,600% from 28 incidents in 2000 to 481 in 2001[8]. A smaller but still substantial increase in hate crimes occurred after the 7/7 London bombings in July 2005. We have found a similar pattern in New Zealand. Rather than rising before the attacks, hate crimes against Muslims instead increased dramatically afterwards. All types of incidents — verbal, online and physical abuse — went up markedly in 2020, the vast majority (35 of 42) after March 15.

Author provided Academic studies show hate crimes sometimes act as a “red flag[6]” of an impending terrorist attack. More commonly, terrorist attacks can spur a rise in hate crimes[7], as members of the group targeted by terrorism exact revenge against the terrorists’ ethnic or religious community. After the September 11 twin-tower attacks in the United States in 2001, hate crimes against Muslims and Arabs increased 1,600% from 28 incidents in 2000 to 481 in 2001[8]. A smaller but still substantial increase in hate crimes occurred after the 7/7 London bombings in July 2005. We have found a similar pattern in New Zealand. Rather than rising before the attacks, hate crimes against Muslims instead increased dramatically afterwards. All types of incidents — verbal, online and physical abuse — went up markedly in 2020, the vast majority (35 of 42) after March 15.  Author provided Most notably, Islamophobic abuse rose by a staggering 1,300% from three to 42 incidents. The largest number (15) occurred in Christchurch, although eight were in Auckland and the remainder distributed throughout the country. These attacks have a major psychological impact, not only on the victims but their community as a whole. Hate crimes against victims of terrorism Our findings mirror research elsewhere[9], which finds hate crimes most often rise after terrorist attacks. But there is a key difference. Elsewhere, these crimes took the form of “vicarious retribution[10]”. Victims were targeted because they were seen to be of the same community as the terrorists. Following the Christchurch attacks, there was a surge in hate crimes against the victims of the attacks. This targeting also occurred elsewhere in the West. In the week after Christchurch, hate crimes against Muslims in the UK rose by 593%[11] with 95 incidents reported to police. Perpetrators mimicked firing a weapon at Muslims or made the noises of a gun as they walked past. These crimes are therefore a perpetuation of the Christchurch attacks. Their increase after March 15 demonstrates that, despite the best intentions of many in New Zealand, the attacks have made the country more, not less, dangerous for Muslims and other minorities. Read more: Four ways social media platforms could stop the spread of hateful content in aftermath of terror attacks[12] The rising incidence of verbal hate crimes against Muslims also underlines the importance of legislating against such intimidation and abuse along religious lines (currently excluded from the Human Rights Act). Resources should be provided to police or other government agencies, or to an independent research centre, to maintain a register of such offences to better monitor patterns in offending. Studies elsewhere have shown more minor forms of identity-related crime sometimes develop into more extreme and ideological violence. Each unpunished attack normalises intimidation and violence and emboldens those with racist or extremist world views. The next government should therefore take these preliminary indications of rising hate crimes extremely seriously.

Author provided Most notably, Islamophobic abuse rose by a staggering 1,300% from three to 42 incidents. The largest number (15) occurred in Christchurch, although eight were in Auckland and the remainder distributed throughout the country. These attacks have a major psychological impact, not only on the victims but their community as a whole. Hate crimes against victims of terrorism Our findings mirror research elsewhere[9], which finds hate crimes most often rise after terrorist attacks. But there is a key difference. Elsewhere, these crimes took the form of “vicarious retribution[10]”. Victims were targeted because they were seen to be of the same community as the terrorists. Following the Christchurch attacks, there was a surge in hate crimes against the victims of the attacks. This targeting also occurred elsewhere in the West. In the week after Christchurch, hate crimes against Muslims in the UK rose by 593%[11] with 95 incidents reported to police. Perpetrators mimicked firing a weapon at Muslims or made the noises of a gun as they walked past. These crimes are therefore a perpetuation of the Christchurch attacks. Their increase after March 15 demonstrates that, despite the best intentions of many in New Zealand, the attacks have made the country more, not less, dangerous for Muslims and other minorities. Read more: Four ways social media platforms could stop the spread of hateful content in aftermath of terror attacks[12] The rising incidence of verbal hate crimes against Muslims also underlines the importance of legislating against such intimidation and abuse along religious lines (currently excluded from the Human Rights Act). Resources should be provided to police or other government agencies, or to an independent research centre, to maintain a register of such offences to better monitor patterns in offending. Studies elsewhere have shown more minor forms of identity-related crime sometimes develop into more extreme and ideological violence. Each unpunished attack normalises intimidation and violence and emboldens those with racist or extremist world views. The next government should therefore take these preliminary indications of rising hate crimes extremely seriously. References

- ^ Human Rights Act 1993 (www.legislation.govt.nz)

- ^ intention to revise the law (www.tvnz.co.nz)

- ^ already covered by the law (www.legislation.govt.nz)

- ^ divisive and dangerous (www.scoop.co.nz)

- ^ Far-right extremists still threaten New Zealand, a year on from the Christchurch attacks (theconversation.com)

- ^ red flag (journals.sagepub.com)

- ^ spur a rise in hate crimes (journals.sagepub.com)

- ^ from 28 incidents in 2000 to 481 in 2001 (www.pri.org)

- ^ research elsewhere (journals.sagepub.com)

- ^ vicarious retribution (journals.sagepub.com)

- ^ rose by 593% (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ Four ways social media platforms could stop the spread of hateful content in aftermath of terror attacks (theconversation.com)