New modelling finds investing in childcare and aged care almost pays for itself

- Written by Janine Dixon, Economist at Centre of Policy Studies, Victoria University

In the absence of an official analysis of the impact of the budget by gender[1] the National Foundation for Australian Women has this morning published its own gender analysis of the budget, across multiple dimensions[2].

It finds the government has invested heavily in things that will mainly benefit men, including apprenticeships and traineeships (two-thirds of which are taken by males), the construction of physical infrastructure, and tax breaks for the purchase of assets that will primarily assist the male-dominated industries of mining and manufacturing.

The female-dominated care sector was largely overlooked, despite the Royal Commission into Aged Care[3] and the Disability Royal Commission[4] highlighting shortcomings in the current system.

Childcare workers were among the first to lose JobKeeper[5].

The extra funding injected into the aged care following tragic impacts of COVID was insufficient to bring the sector to a four star quality rating[6].

The experts believe the budget is a lost opportunity to maximise employment growth, to invest in the (social) infrastructure that will most boost the economy and to address the problems with female-dominated paid and unpaid work[7] exposed by COVID-19.

Care boosts employment

Published with the National Foundation for Australian Women’s analysis is new modelling[8] by the Victoria University Centre of Policy Studies on government investment in the care sector.

It examines what would happen if the government increased funding enough to boost the wages of personal and child care workers and to lift capacity to the point where it met unmet demand.

More than 900,000 Australians who provide unpaid care to the elderly, disabled, and children aged under five say they would like more hours in paid employment[9].

Read more: Labor's childcare plan may get more women into work. Now what about quality and educators' pay?[10]

The modelling finds that the investment in the care economy needed to enable each of these unpaid carers to work an extra 10 hours a week in paid employment has a significant economic payoff, increasing labour supply by 2%.

By 2030 the extra labour supply would be fully absorbed into employment. Annual GDP per person would be $1,270 higher, or more than $30 billion in aggregate.

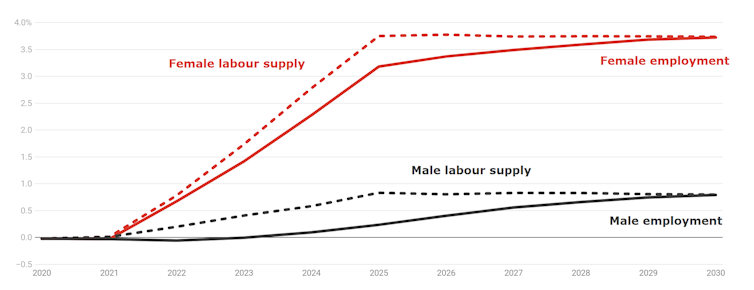

Women’s paid employment would be 3.75% greater than it would have been if no action had been taken. Men’s employment would be more than 0.75% above the no-action base case.

Employment and labour supply impacts of modelled extra spending on care

Percentage deviation from base.

Centre of Policy Studies, Victoria University[11]

Percentage deviation from base.

Centre of Policy Studies, Victoria University[11]

The average incomes of both women and men would be higher, although women’s incomes would be higher by a greater margin.

A boost would almost pay for itself

The budgetary cost of the policy would be largely offset by increased economic growth which would underpin greater revenue collection from income taxes and the goods and services tax.

When fully running, the net cost to the budget would be less than one fifth of the direct cost.

Government investment in physical infrastructure helps in two ways – it provides construction jobs and a useful piece of infrastructure to support future economic activity.

Read more: High-viz, narrow vision: the budget overlooks the hardest hit in favour of the hardest hats[12]

Investment in care helps in three ways:

It stimulates jobs and better conditions in the care sector, a worthy outcome in itself.

It provides economic stimulus to all sectors by freeing people up to participate in the labour market, an impact that cannot be achieved by providing stimulus to other sectors, such as manufacturing, for example.

And it addresses female economic disadvantage by reducing the wage gap and changing the circumstances that often set limits on what women can achieve in their careers.

There’s a new budget around the corner

While the analysis shows the population on average would be better off with an expanded care sector, it says nothing about how to reform access to subsidised or government-funded care.

The system is complicated, as are the (dis)incentives to work resulting from the present tax and charging arrangements[13].

Read more: Politics with Michelle Grattan: economist Danielle Wood on Australia's 'blokey' budget[14]

However charged for, extra spending on childcare, aged care and disability care would produce an bigger bang for the buck than most of the extra spending announced in the budget, as well as producing better outcomes for women.

There’s a budget update around the corner, in December, and a new budget due in May. If extra spending is needed, there’s an opportunity to do it in a way that would really help and almost pay for itself.

References

- ^ official analysis of the impact of the budget by gender (theconversation.com)

- ^ multiple dimensions (nfaw.org)

- ^ Royal Commission into Aged Care (theconversation.com)

- ^ Disability Royal Commission (disability.royalcommission.gov.au)

- ^ among the first to lose JobKeeper (theconversation.com)

- ^ four star quality rating (www.equityeconomics.com.au)

- ^ paid and unpaid work (www.un.org)

- ^ new modelling (nfaw.org)

- ^ like more hours in paid employment (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Labor's childcare plan may get more women into work. Now what about quality and educators' pay? (theconversation.com)

- ^ Centre of Policy Studies, Victoria University (nfaw.org)

- ^ High-viz, narrow vision: the budget overlooks the hardest hit in favour of the hardest hats (theconversation.com)

- ^ tax and charging arrangements (theconversation.com)

- ^ Politics with Michelle Grattan: economist Danielle Wood on Australia's 'blokey' budget (theconversation.com)

Authors: Janine Dixon, Economist at Centre of Policy Studies, Victoria University