China's leaders are strong and emboldened. It's wrong to see them as weak and insecure

- Written by Saul Eslake, Vice-Chancellor’s Fellow, University of Tasmania

There’s an emerging view that China’s belligerent approach and “torching” of diplomatic relationships with the wider world is a sign of “insecurity and weakness”; that its economic growth is “unsustainable”; and that “everyone in the top ranks of the Chinese Communist Party” knows the day is coming when “China’s entire economic structure and strategic position crumbles”.

These views are drawn from an essay by Peter Zeihan entitled A Failure of Leadership: The Beginning of the End of China[1].

He describes himself as a geopolitical strategist whose work history includes a stint working for the US State Department in Australia[2].

He is hardly the first person[3] to say these sorts of things, and I suspect he won’t be the first to be wrong about them, at least for quite a while.

That’s not to say he doesn’t draw on facts. China has been extraordinarily profligate in its use of capital, and has become progressively more so over the last two decades.

Paul Krugman (1994) famously made the same point about the then rapidly-growing smaller East Asian economies a few years before the Asian financial crisis in The Myth of Asia’s Miracle[4].

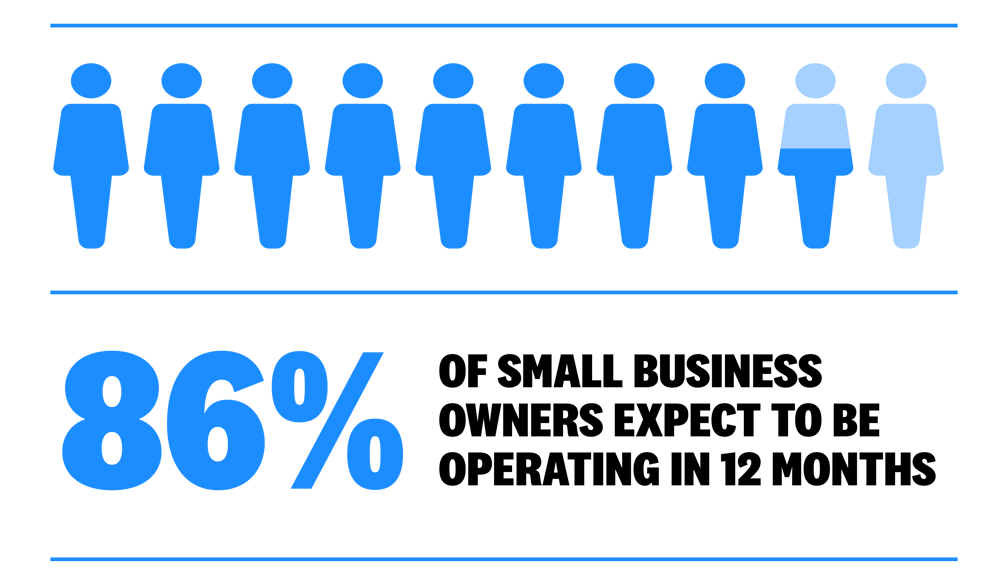

China is certainly laden with debt

Nor is there any denying that China has an enormous amount of debt relative to the size of its economy, especially for what is still in many ways a “developing” economy.

Debt as a percentage of GDP

December 2019. Bank for International Settlements, Credit to the non-financial sector[5]

December 2019. Bank for International Settlements, Credit to the non-financial sector[5]

But, and this is an important “but”, most of that debt is owed by state-owned enterprises to state-owned banks – which can be thought of as two entries on opposing sides of the same balance sheet, that of the People’s Republic of China.

If a lot of that were to turn “bad”, which is by no means impossible, then the ensuing “crisis” could be solved by writing it off, and then re-capitalising the state-owned banks by drawing down on the foreign exchange reserves of the People’s Bank of China.

China has actually done this twice before, in the late 1990s[6] as part of the state-owned enterprise reforms pushed through by then-Premier Zhu Rongji, and again between 2003 and 2005[7], when the big four state-owned banks were “cleaned up” ahead of their very partial privatisation and listing on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

Read more: Journalists have become diplomatic pawns in China's relations with the West, setting a worrying precedent[8]

The “bad assets” were transferred into an entity called Central Huijin which subsequently became the nucleus of China’s sovereign wealth fund, the China Investment Corporation[9].

An unknown question is whether the People’s Bank of China’s foreign exchange reserves would be sufficient for what would now be a much larger task.

It lost one quarter of its reserves (almost US$1 trillion) defending its currency between June 2014 and December 2016, after which it imposed very strict controls on capital outflows, which have remained in force ever since and are easier to maintain in an authoritarian regime that knows how to deploy modern technology for surveillance purposes[10] than in other countries that have resorted to capital controls such as Argentina.

But it is aware of the risks…

Since that time, the ubiquitous “Chinese authorities”, as they are usually referred to by Western economists, have been acutely aware[11] of the risks to financial stability posed by the growth of so-called shadow banks and the way Chinese banks have become more dependent on wholesale funding and less on deposits; as US and European banks did, to a much greater extent, in the years leading up to the global financial crisis.

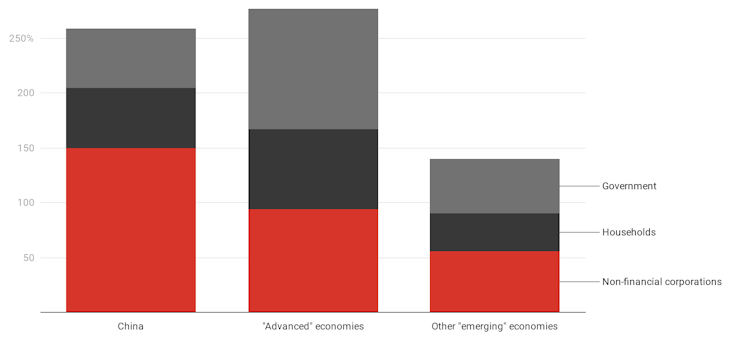

That’s in part why China’s economic growth rate has been steadily slowing over the the past decade, from an average of 11.3% in the five years to 2009, to 8.5% in the five years to 2014, and to 6.6% in the five years to 2019.

Read more: Book Review: Hidden Hand – Exposing How the Chinese Communist Party is Reshaping the World[12]

Another important reason has been that China’s working-age population peaked in 2014 and has since shrunk by almost 1.5%.

It also helps explain why the People’s Bank of China hasn’t done nearly as much monetary stimulus as it did during and after the financial crisis or in 2015-16.

There hasn’t been a significant acceleration in credit growth in recent months nor has there been a surge in property development or prices, as there would have been if the People’s Bank of China had unleashed another wave of credit.

Average annual growth in China’s real GDP over five-year intervals

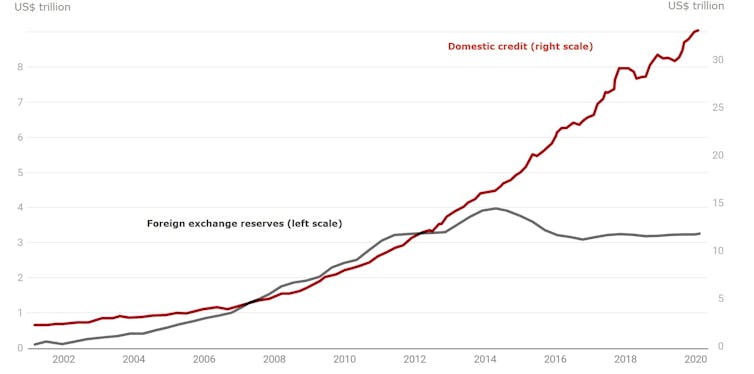

Source: China National Bureau of Statistics China’s authorities are doing more fiscal stimulus than they did 12 years ago, although it is in different forms[13] to the construction-intensive programs it implemented then. The potentially most worrying development – albeit not from the perspective of the next year or so – is the one depicted in this chart, which shows a marked divergence between the level of foreign exchange reserves and the rate of growth in domestic credit. China’s domestic credit and foreign exchange reserves

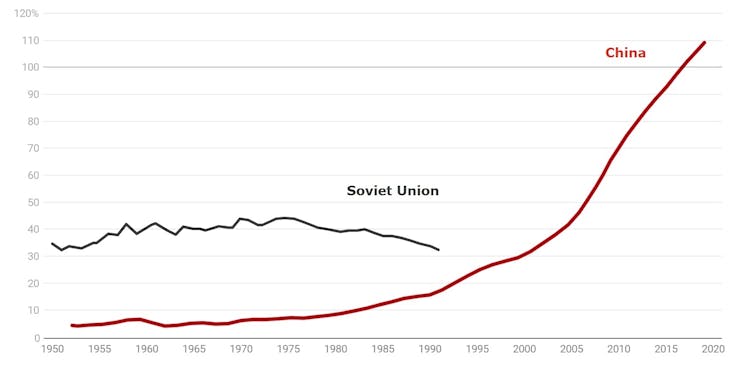

Source: China National Bureau of Statistics China’s authorities are doing more fiscal stimulus than they did 12 years ago, although it is in different forms[13] to the construction-intensive programs it implemented then. The potentially most worrying development – albeit not from the perspective of the next year or so – is the one depicted in this chart, which shows a marked divergence between the level of foreign exchange reserves and the rate of growth in domestic credit. China’s domestic credit and foreign exchange reserves  Credit converted from yuan to US$ at month-average exchange rates. People’s Bank of China; Jonathan Anderson (2020); author’s calculations.[14] For a fixed exchange rate system to be sustainable, the two ordinarily need to maintain a fairly close and stable relationship – which they do under a “currency board” like the one Hong Kong has had since 1984 (or that the Baltic states had before joining the euro, and which Bulgaria still has) where the monetary authority is explicitly precluded from issuing currency unless it is backed by foreign exchange reserves (or, in Hong Kong’s case, reserves plus the Land Fund[15]). China’s foreign exchange rate is of course no longer completely fixed, but rather is “carefully managed” around a peg to a trade-weighted index[16] (as the Australian dollar used to be between 1976 and 1983). But the People’s Bank of China’s capacity to maintain that peg is dependent on the credibility of its implicit promise to buy or sell its currency in whatever quantity is required to keep the exchange rate close to the peg. …and good at limiting capital flight Obviously China can sell its currency in whatever quantities it likes, since it are the ultimate source of its currency, and so can always prevent it from appreciating more than it wants (as can any country which is prepared to accept the potentially inflationary consequences of a sudden large increase in its domestic money supply). But China doesn’t own or operate a US dollar factory, so it can only stave off a big depreciation for as long as it has sufficient foreign exchange reserves to satisfy everyone who wants to convert its currency into foreign dollars. And that’s why the capital controls are so important at the moment: because they limit the demand for foreign currencies enough to ensure that the level of foreign exchange reserves is more than adequate, and widely regarded as such. Read more: Politics with Michelle Grattan: Clive Hamilton and Richard McGregor on Australia-China relations[17] If something were to happen that resulted in a tsunami of capital outflows, and the Chinese authorities didn’t have any other ways of stopping it (such as confiscating the assets of or imprisoning or executing people who tried to get their money out of the country, something which I am sure they might not baulk at) there would be a “currency crisis”; the Chinese renminbi fall a lot, and the weakness in the domestic financial system (resulting from the accumulation of so much bad debt) would be fully exposed. But you have to ask, how likely is that in the foreseeable future? I can’t see any reason to answer that question with anything other than “not very”. It’s worth remembering in this context that the lesson which the Chinese Communist Party drew from the collapse of the Soviet empire is that brutal authoritarian regimes can only survive, once they have clearly failed to deliver on the promise of delivering ongoing improvements in people’s well-being, for as long as they are willing to kill their own people in sufficient numbers to quieten resistance, or for as long as there is someone else who is willing and able to do it for them. China is authoritarian… The Communist regimes of Eastern Europe, most of which had been demonstrably willing to shoot their own people (or allow the Soviets in to do it for them) at various times in the 1950s, 1960s and early 1980s, collapsed when they lost the will to shoot their own people, and the Soviets under Gorbachev lost the will to do it for them[18]. And the Soviet Union itself collapsed in 1991 when neither Gorbachev, nor the cabal of drunken fools who briefly tried to overthrow him in August of that year, were willing to shoot their own people. It is worth noting in passing that Vladimir Putin has repeatedly demonstrated that he has no such scruples about killing his own people[19] – whether they be ordinary Russians in high-rise apartments around Moscow, middle-class Muscovites attending the theatre, school children and their parents in Beslan, troublesome journalists, former KGB agents living in the UK, lawyers for aggrieved hedge fund managers, or prominent opposition figures. Read more: I kept silent to protect my colleague and friend, Kylie Moore-Gilbert. But Australia's quiet diplomatic approach is not working[20] By contrast with their contemporaries in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, Deng Xiaoping and Li Peng demonstrated that they were perfectly relaxed[21] about the idea of shooting, or running over with tanks, large numbers of their own people in order to ensure that they remained in power – and even more competent than Josef Stalin in air-brushing[22] those events out of the collective memory of the people who remained alive. And I suspect nothing has changed, at least in that regard, since then. Indeed Xi Jinping has repeatedly shown that he’s prepared to do whatever is required to entrench the Chinese Communist Party as the source of all power[23] in China, to sideline[24] potential rivals and to remain in office for as long as he is capable of drawing breath (not least because he is smart enough to know that he has made a lot of enemies, and that they would take their revenge[25] on him and his family and supporters as soon as he was out of power – as Putin did to Boris Yeltsin’s wealthy supporters). Far from feeling “weak and insecure”, I think China feels strong and emboldened – not only by its apparent success in stopping the spread of the virus (admittedly after a number of initial serious missteps[26]) but also by the manifest incompetence of the US administration in dealing with COVID-19, and its almost complete abdication of its traditional global leadership role (something that, to be fair, didn’t start under Trump). Read more: The China-US rivalry is not a new Cold War. It is way more complex and could last much longer[27] That’s why Xi has explicitly discarded Deng Xiaoping’s dictum that China should “hide your capacities and bide your time” – much as, Woodrow Wilson and, more forcefully, Roosevelt and his successors all the way to George W Bush – were prepared to discard George Washington’s advice, in his 1796 farewell address (which was actually written by Alexander Hamilton) to “avoid foreign entanglements[28]”. Xi (and, as far as one can tell, most of the Chinese population) think that “now” is China’s “time”. That’s what he means by phrases like “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation[29]” and the “Chinese dream”. And of course China’s economy, notwithstanding its burden of debt, is much stronger than the Soviet Union’s ever was. Size of Soviet Union and China economies in relation to the United States

Credit converted from yuan to US$ at month-average exchange rates. People’s Bank of China; Jonathan Anderson (2020); author’s calculations.[14] For a fixed exchange rate system to be sustainable, the two ordinarily need to maintain a fairly close and stable relationship – which they do under a “currency board” like the one Hong Kong has had since 1984 (or that the Baltic states had before joining the euro, and which Bulgaria still has) where the monetary authority is explicitly precluded from issuing currency unless it is backed by foreign exchange reserves (or, in Hong Kong’s case, reserves plus the Land Fund[15]). China’s foreign exchange rate is of course no longer completely fixed, but rather is “carefully managed” around a peg to a trade-weighted index[16] (as the Australian dollar used to be between 1976 and 1983). But the People’s Bank of China’s capacity to maintain that peg is dependent on the credibility of its implicit promise to buy or sell its currency in whatever quantity is required to keep the exchange rate close to the peg. …and good at limiting capital flight Obviously China can sell its currency in whatever quantities it likes, since it are the ultimate source of its currency, and so can always prevent it from appreciating more than it wants (as can any country which is prepared to accept the potentially inflationary consequences of a sudden large increase in its domestic money supply). But China doesn’t own or operate a US dollar factory, so it can only stave off a big depreciation for as long as it has sufficient foreign exchange reserves to satisfy everyone who wants to convert its currency into foreign dollars. And that’s why the capital controls are so important at the moment: because they limit the demand for foreign currencies enough to ensure that the level of foreign exchange reserves is more than adequate, and widely regarded as such. Read more: Politics with Michelle Grattan: Clive Hamilton and Richard McGregor on Australia-China relations[17] If something were to happen that resulted in a tsunami of capital outflows, and the Chinese authorities didn’t have any other ways of stopping it (such as confiscating the assets of or imprisoning or executing people who tried to get their money out of the country, something which I am sure they might not baulk at) there would be a “currency crisis”; the Chinese renminbi fall a lot, and the weakness in the domestic financial system (resulting from the accumulation of so much bad debt) would be fully exposed. But you have to ask, how likely is that in the foreseeable future? I can’t see any reason to answer that question with anything other than “not very”. It’s worth remembering in this context that the lesson which the Chinese Communist Party drew from the collapse of the Soviet empire is that brutal authoritarian regimes can only survive, once they have clearly failed to deliver on the promise of delivering ongoing improvements in people’s well-being, for as long as they are willing to kill their own people in sufficient numbers to quieten resistance, or for as long as there is someone else who is willing and able to do it for them. China is authoritarian… The Communist regimes of Eastern Europe, most of which had been demonstrably willing to shoot their own people (or allow the Soviets in to do it for them) at various times in the 1950s, 1960s and early 1980s, collapsed when they lost the will to shoot their own people, and the Soviets under Gorbachev lost the will to do it for them[18]. And the Soviet Union itself collapsed in 1991 when neither Gorbachev, nor the cabal of drunken fools who briefly tried to overthrow him in August of that year, were willing to shoot their own people. It is worth noting in passing that Vladimir Putin has repeatedly demonstrated that he has no such scruples about killing his own people[19] – whether they be ordinary Russians in high-rise apartments around Moscow, middle-class Muscovites attending the theatre, school children and their parents in Beslan, troublesome journalists, former KGB agents living in the UK, lawyers for aggrieved hedge fund managers, or prominent opposition figures. Read more: I kept silent to protect my colleague and friend, Kylie Moore-Gilbert. But Australia's quiet diplomatic approach is not working[20] By contrast with their contemporaries in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, Deng Xiaoping and Li Peng demonstrated that they were perfectly relaxed[21] about the idea of shooting, or running over with tanks, large numbers of their own people in order to ensure that they remained in power – and even more competent than Josef Stalin in air-brushing[22] those events out of the collective memory of the people who remained alive. And I suspect nothing has changed, at least in that regard, since then. Indeed Xi Jinping has repeatedly shown that he’s prepared to do whatever is required to entrench the Chinese Communist Party as the source of all power[23] in China, to sideline[24] potential rivals and to remain in office for as long as he is capable of drawing breath (not least because he is smart enough to know that he has made a lot of enemies, and that they would take their revenge[25] on him and his family and supporters as soon as he was out of power – as Putin did to Boris Yeltsin’s wealthy supporters). Far from feeling “weak and insecure”, I think China feels strong and emboldened – not only by its apparent success in stopping the spread of the virus (admittedly after a number of initial serious missteps[26]) but also by the manifest incompetence of the US administration in dealing with COVID-19, and its almost complete abdication of its traditional global leadership role (something that, to be fair, didn’t start under Trump). Read more: The China-US rivalry is not a new Cold War. It is way more complex and could last much longer[27] That’s why Xi has explicitly discarded Deng Xiaoping’s dictum that China should “hide your capacities and bide your time” – much as, Woodrow Wilson and, more forcefully, Roosevelt and his successors all the way to George W Bush – were prepared to discard George Washington’s advice, in his 1796 farewell address (which was actually written by Alexander Hamilton) to “avoid foreign entanglements[28]”. Xi (and, as far as one can tell, most of the Chinese population) think that “now” is China’s “time”. That’s what he means by phrases like “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation[29]” and the “Chinese dream”. And of course China’s economy, notwithstanding its burden of debt, is much stronger than the Soviet Union’s ever was. Size of Soviet Union and China economies in relation to the United States  Comparison with USSR and based on estimates of GDP in 1990 US dollars at purchasing power parities; comparison with China based on official estimates of GDP in 2019 US dollars at purchasing power parities. Sources: Conference Board Total Economy Database; author’s calculations[30] The closest the Soviet economy ever got to matching the United States’ was between 1974 and 1976 when it reached 44% of US gross domestic product. By the time Gorbachev took office in 1985 it was down to 38%, and in 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed, its GDP was less than a third of the United States. By contrast, measured in the same way, China’s economy surpassed the US economy in 2017, and this year is likely to be at least 10% bigger than the US (when compared using actual buying power – “purchasing power parity[31]” – rather than the official exchange rate which shows the Chinese economy only about two-thirds of the US economy which is still a lot closer than the Soviet Union got). …and its least-dependent in decades It’s perhaps also worth noting that China isn’t really all that dependent on exports any more – in 2019 exports accounted for only 18.4%[32] of China’s economy, down from a peak of 36% in 2006 and less than at any time since 1991. Big economies, like China’s now is, tend to be relatively “closed”, which is why exports only represent 12% of the US GDP and 18.5% of Japan’s compared to 24% of Australia’s. So, to summarise, I can’t agree with the proposition that China’s growth model is unsustainable and its leadership weak and insecure. Of course, in the long run (when, as the economist John Maynard Keynes famously said, we’re all dead[33]), it might turn out to be right. China’s government and its growth model might collapse. But I’m not going to lie awake at night wondering whether it’s happened.

Comparison with USSR and based on estimates of GDP in 1990 US dollars at purchasing power parities; comparison with China based on official estimates of GDP in 2019 US dollars at purchasing power parities. Sources: Conference Board Total Economy Database; author’s calculations[30] The closest the Soviet economy ever got to matching the United States’ was between 1974 and 1976 when it reached 44% of US gross domestic product. By the time Gorbachev took office in 1985 it was down to 38%, and in 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed, its GDP was less than a third of the United States. By contrast, measured in the same way, China’s economy surpassed the US economy in 2017, and this year is likely to be at least 10% bigger than the US (when compared using actual buying power – “purchasing power parity[31]” – rather than the official exchange rate which shows the Chinese economy only about two-thirds of the US economy which is still a lot closer than the Soviet Union got). …and its least-dependent in decades It’s perhaps also worth noting that China isn’t really all that dependent on exports any more – in 2019 exports accounted for only 18.4%[32] of China’s economy, down from a peak of 36% in 2006 and less than at any time since 1991. Big economies, like China’s now is, tend to be relatively “closed”, which is why exports only represent 12% of the US GDP and 18.5% of Japan’s compared to 24% of Australia’s. So, to summarise, I can’t agree with the proposition that China’s growth model is unsustainable and its leadership weak and insecure. Of course, in the long run (when, as the economist John Maynard Keynes famously said, we’re all dead[33]), it might turn out to be right. China’s government and its growth model might collapse. But I’m not going to lie awake at night wondering whether it’s happened. References

- ^ A Failure of Leadership: The Beginning of the End of China (zeihan.com)

- ^ US State Department in Australia (zeihan.com)

- ^ first person (cdn.theconversation.com)

- ^ The Myth of Asia’s Miracle (www.brmandel.com)

- ^ Bank for International Settlements, Credit to the non-financial sector (www.bis.org)

- ^ late 1990s (cdn.theconversation.com)

- ^ between 2003 and 2005 (cdn.theconversation.com)

- ^ Journalists have become diplomatic pawns in China's relations with the West, setting a worrying precedent (theconversation.com)

- ^ China Investment Corporation (www.china-inv.cn)

- ^ deploy modern technology for surveillance purposes (www.theatlantic.com)

- ^ acutely aware (www.ft.com)

- ^ Book Review: Hidden Hand – Exposing How the Chinese Communist Party is Reshaping the World (theconversation.com)

- ^ different forms (www.china-briefing.com)

- ^ People’s Bank of China; Jonathan Anderson (2020); author’s calculations. (emadvisorsgroup.com)

- ^ Land Fund (cdn.theconversation.com)

- ^ peg to a trade-weighted index (www.imf.org)

- ^ Politics with Michelle Grattan: Clive Hamilton and Richard McGregor on Australia-China relations (theconversation.com)

- ^ to do it for them (www.goodreads.com)

- ^ no such scruples about killing his own people (cdn.theconversation.com)

- ^ I kept silent to protect my colleague and friend, Kylie Moore-Gilbert. But Australia's quiet diplomatic approach is not working (theconversation.com)

- ^ perfectly relaxed (cdn.theconversation.com)

- ^ air-brushing (global.oup.com)

- ^ all power (www.scmp.com)

- ^ sideline (global.oup.com)

- ^ revenge (www.fpri.org)

- ^ initial serious missteps (www.lowyinstitute.org)

- ^ The China-US rivalry is not a new Cold War. It is way more complex and could last much longer (theconversation.com)

- ^ avoid foreign entanglements (cdn.theconversation.com)

- ^ the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation (www.theasanforum.org)

- ^ Sources: Conference Board Total Economy Database; author’s calculations (www.conference-board.org)

- ^ purchasing power parity (www.investopedia.com)

- ^ 18.4% (data.worldbank.org)

- ^ we’re all dead (en.wikiquote.org)

Authors: Saul Eslake, Vice-Chancellor’s Fellow, University of Tasmania