Why the coronavirus shouldn't stand in the way of the next wage increase

- Written by Michael Keating, Visiting Fellow, College of Business & Economics, Australian National University

In the early 1970s, when rising inflation and unemployment tore through the economy, someone coined the aphorism “one man’s wage increase is another man’s job” (unfortunately, most of the talk was about men in those days).

It took off, in part because it appealed to common sense. If the price of something (workers) went up, employers would want would want less of them (workers).

In Harper, former head of the Fair Pay Commission.

ALAN PORRITT/AAP

In Harper, former head of the Fair Pay Commission.

ALAN PORRITT/AAP

Employers have used it to oppose every wage increase or improvement in working conditions in history, and still are.

Sometimes they are supported by widely respected economists, such as Ian Harper[1], who as head of the Fair Pay Commission[2] in 2009 delivered Australia’s last freeze in minimum wages amid forecasts that unemployment was about to climb.

Now he and other economists are calling for another freeze, for the sake of jobs[3], in the downturn caused by the coronavirus.

Wages are more than prices

But the price of labour is different to other prices. While it represents the cost of buying a service, it also represents an income, one that bundled together with other incomes pays for the service.

When wages grow, spending grows (so-called “aggregate demand”), and so does the economy, as measured by gross domestic product.

Nevertheless, the standard neoclassical growth model used by the treasury and Reserve Bank doesn’t recognise this. Instead, it assumes that over the medium term economic growth is entirely determined by supply rather than demand, and that supply is a function of the three Ps: productivity, population and workforce participation.

Read more: Vital Signs: Amid talk of recessions, our progress on wages and unemployment is almost non-existent[4]

Demand is said to merely cause short term fluctuations around the medium term growth path, and it is thought to be the job of monetary and fiscal policy to iron out the fluctuations to avoid unnecessary inflation or unemployment.

There are a number of other peculiar things about the model. It assumes that there are constant returns to scale, that technological progress favours neither labour nor capital, and there is perfect competition.

These assumptions effectively mean the distribution of income between wages and profits is constant and can be ignored.

The model that continually gets it wrong

Fluctuations in wages growth are presumed to be cyclical, amenable to correction by by monetary policy (interest rates), with fiscal policy (tax and government spending) held in reserve.

The model hasn’t performed well.

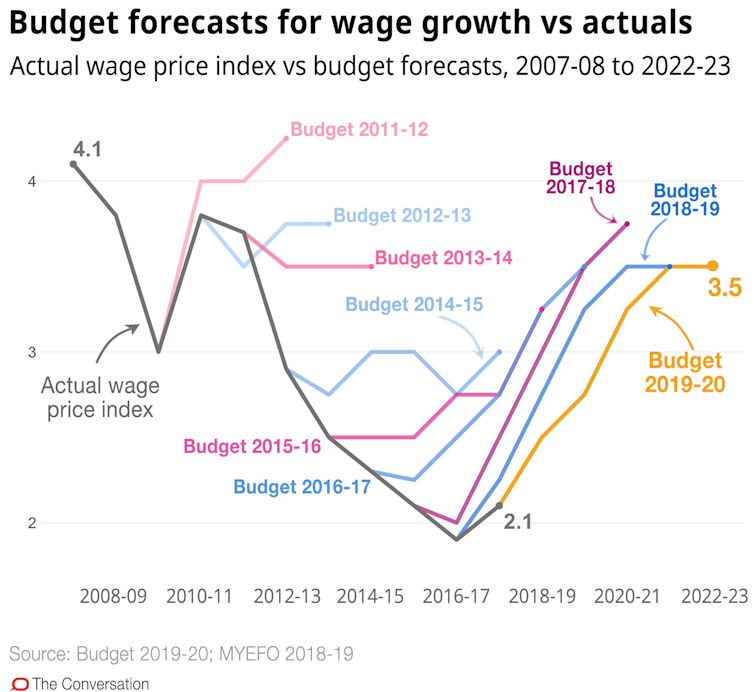

Over the past decade the treasury and Reserve Bank have persistently overestimated wage growth.

Wage growth has almost halved during the time it was overestimated, and it seems likely this is related to a similar decline in the growth of GDP.

Treasury and the Reserve Bank overestimated wage growth because, when combined, the three Ps of productivity, population and workforce participation were growing strongly.

Their thinking was that if wage growth wasn’t climbing as expected, that was mainly due to a cyclical downturn. All that was needed were some interest rate cuts.

We’ve had 17 interest rate cuts in the past decade the treasury and Reserve Bank have continued to forecast wage growth while taking the cash rate all the way down from 4.75% to close to zero.

There are better models

A better model, used by post-Keynesian economists, treats economic growth as being determined by aggregate demand, both in the short and longer terms. Aggregate demand can be either wage or profit-led.

Wage growth can lead to growth in consumer spending, profit growth can lead to growth in business investment.

Profit growth can be enhanced by changes in the profit share of income, which is the other side of the wage share of income. When the wage share of income goes up, the profit share goes down.

Read more:

Budget explainer: why is Australia's wage growth so sluggish?[5]

But profit growth can also be affected by capacity utilisation, which is the extent to which factories and the like are operating at their full capacity. The more consumers spend, the greater the rate of capacity utilisation and the greater are profits.

Very large increases in real wages can most certainly dent economic growth.

They cut profits and business investment by more than they increase consumer demand and capacity utilisation, as happened in the early 1970s when between 1973 and 1975 nominal wages increased at an average annual pace of 23.2 per cent and real wages increased at an average pace of 8.9 per cent - way ahead of annual productivity growth of 1.3 per cent.

But mostly, wage rises boost consumer demand by more than they cut business investment.

Indeed, they can actually push business investment higher. This is because profits are often more responsive to the increase in capacity utilisation that results from increased consumer demand than to a lower profit share.

We’ll need to boost incomes, if not wages

This seems to explain the economic stagnation we have experienced since the global financial crisis. Low wage growth has held back consumer demand, which has also held back business investment.

There are three possible policy responses.

One is to boost household incomes in a way that doesn’t involve boosting wages, perhaps by government payments and/or tax relief. A downside is that they add to the budget deficit and public debt.

Another is to try and increase wages. Tools could include include government support for higher wages, starting with support for a modest increase in the minimum wage case now before the Fair Work Commission[6].

Read more:

We should simplify our industrial relations system, but not in the way big business wants[7]

Longer term, a more effective and lasting increase in wages could be achieved by better education and training to better skill workers. These proposed courses of action are not mutually exclusive. We will probably need to adopt all three.

But we will need to understand that improving our economic circumstances will require a combination of wage increases and increased government support.

The more the government opposes wage increases, the more pressure there will be for it to increase spending and/or offer more tax relief if we want the economy to grow at its potential and to lift that potential.

These thoughts are developed in Low Wage Growth: Why It Matters and How to Fix It[8], Stephen Bell and Michael Keating, Australian Economic Review, December 2019.

Treasury and the Reserve Bank overestimated wage growth because, when combined, the three Ps of productivity, population and workforce participation were growing strongly.

Their thinking was that if wage growth wasn’t climbing as expected, that was mainly due to a cyclical downturn. All that was needed were some interest rate cuts.

We’ve had 17 interest rate cuts in the past decade the treasury and Reserve Bank have continued to forecast wage growth while taking the cash rate all the way down from 4.75% to close to zero.

There are better models

A better model, used by post-Keynesian economists, treats economic growth as being determined by aggregate demand, both in the short and longer terms. Aggregate demand can be either wage or profit-led.

Wage growth can lead to growth in consumer spending, profit growth can lead to growth in business investment.

Profit growth can be enhanced by changes in the profit share of income, which is the other side of the wage share of income. When the wage share of income goes up, the profit share goes down.

Read more:

Budget explainer: why is Australia's wage growth so sluggish?[5]

But profit growth can also be affected by capacity utilisation, which is the extent to which factories and the like are operating at their full capacity. The more consumers spend, the greater the rate of capacity utilisation and the greater are profits.

Very large increases in real wages can most certainly dent economic growth.

They cut profits and business investment by more than they increase consumer demand and capacity utilisation, as happened in the early 1970s when between 1973 and 1975 nominal wages increased at an average annual pace of 23.2 per cent and real wages increased at an average pace of 8.9 per cent - way ahead of annual productivity growth of 1.3 per cent.

But mostly, wage rises boost consumer demand by more than they cut business investment.

Indeed, they can actually push business investment higher. This is because profits are often more responsive to the increase in capacity utilisation that results from increased consumer demand than to a lower profit share.

We’ll need to boost incomes, if not wages

This seems to explain the economic stagnation we have experienced since the global financial crisis. Low wage growth has held back consumer demand, which has also held back business investment.

There are three possible policy responses.

One is to boost household incomes in a way that doesn’t involve boosting wages, perhaps by government payments and/or tax relief. A downside is that they add to the budget deficit and public debt.

Another is to try and increase wages. Tools could include include government support for higher wages, starting with support for a modest increase in the minimum wage case now before the Fair Work Commission[6].

Read more:

We should simplify our industrial relations system, but not in the way big business wants[7]

Longer term, a more effective and lasting increase in wages could be achieved by better education and training to better skill workers. These proposed courses of action are not mutually exclusive. We will probably need to adopt all three.

But we will need to understand that improving our economic circumstances will require a combination of wage increases and increased government support.

The more the government opposes wage increases, the more pressure there will be for it to increase spending and/or offer more tax relief if we want the economy to grow at its potential and to lift that potential.

These thoughts are developed in Low Wage Growth: Why It Matters and How to Fix It[8], Stephen Bell and Michael Keating, Australian Economic Review, December 2019.

References

- ^ Ian Harper (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ Fair Pay Commission (web.archive.org)

- ^ for the sake of jobs (www.afr.com)

- ^ Vital Signs: Amid talk of recessions, our progress on wages and unemployment is almost non-existent (theconversation.com)

- ^ Budget explainer: why is Australia's wage growth so sluggish? (theconversation.com)

- ^ Fair Work Commission (www.fwc.gov.au)

- ^ We should simplify our industrial relations system, but not in the way big business wants (theconversation.com)

- ^ Low Wage Growth: Why It Matters and How to Fix It (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

Authors: Michael Keating, Visiting Fellow, College of Business & Economics, Australian National University