As the COVID cash glut comes to an end, the Reserve Bank is changing the way it sets and maintains interest rates

- Written by Isaac Gross, Lecturer in Economics, Monash University

Every six weeks, the Reserve Bank of Australia sets the “cash rate[1]”, affecting the interest rates paid on every Australian mortgage and savings account.

Like any price mechanism, the cost of borrowing money is determined by supply and demand – how much cash is in the banking system, and how much has been borrowed at any one time.

With powers to manipulate this supply, the Reserve Bank is able to set and precisely achieve its target cash rate.

But during the pandemic, an abundance of cash forced the Reserve Bank to quickly change its method for doing so. Now, that method is set to change again[2].

The traditional method – ‘scarce reserves’

When you make a purchase, pay a bill or send money to a friend, it’s quite likely the transaction involves transmitting money between different banks. Around the country, these transactions add up to a colossal amount of money – more than A$200 billion daily[3] – and banks need to hold enough money in reserve to settle their books at the end of each day.

Banks hold these reserves in large “exchange settlement accounts” with our central bank – the Reserve Bank.

But managing these accounts gives the Reserve Bank a powerful lever for setting and adjusting interest rates.

Before the pandemic, the Reserve Bank operated under a “scarce reserves” system. Cash reserves held by banks to enable interbank transactions were kept relatively small.

Because these funds were in short supply, banks would have to actively lend them to each other to ensure they all had enough money to settle transactions at the end of each day. The interest rate on these loans was Australia’s effective cash rate.

Read more: Interest rates are expected to drop but trying to out-think the market won't guarantee getting a good deal[5]

To maintain a set cash rate under a scarce reserves system, the Reserve Bank had to conduct “open market operations” to continuously fine-tune the supply of money.

If it wanted to raise the cash rate, it would sell securities (such as bonds) to commercial banks. This drew money out of the banking system and reduced the level of cash reserves.

Conversely, to lower the cash rate, it would buy securities from the commercial banks, adding money back into the system and increasing total cash reserves.

This could be a tricky process, as it required the Reserve Bank to continuously and accurately estimate the demand for cash reserves. But the central bank managed it rather well, in part because commercial banks would almost always follow their lead and lend at the target cash rate.

The main downside of this approach was that the limited supply of funds available to the banking sector increased the risk that individual banks could face liquidity problems – not having enough cash to maintain their operations.

The pandemic saw banks flush with cash

During the pandemic, however, the Reserve Bank flooded the financial system with additional funds to support the Australian economy in a downturn.

The banks suddenly had plenty of cash, so there was no need for them to lend between themselves. In central banking, this is known as a system of “abundant reserves”.

In this environment, the only way the Reserve Bank could later get the banks to lift interest rates was by offering to pay them a positive interest rate themselves. The Reserve Bank would simply increase the interest rate paid to the banks on their exchange settlement accounts, who would in turn pass that rate on to Australian households.

This is a much simpler method of lifting interest rates than continuous open-market operations, but it’s expensive. Interest rate increases over the past two years have cost the Reserve Bank more than A$40 billion[7].

A third option – ‘ample reserves’

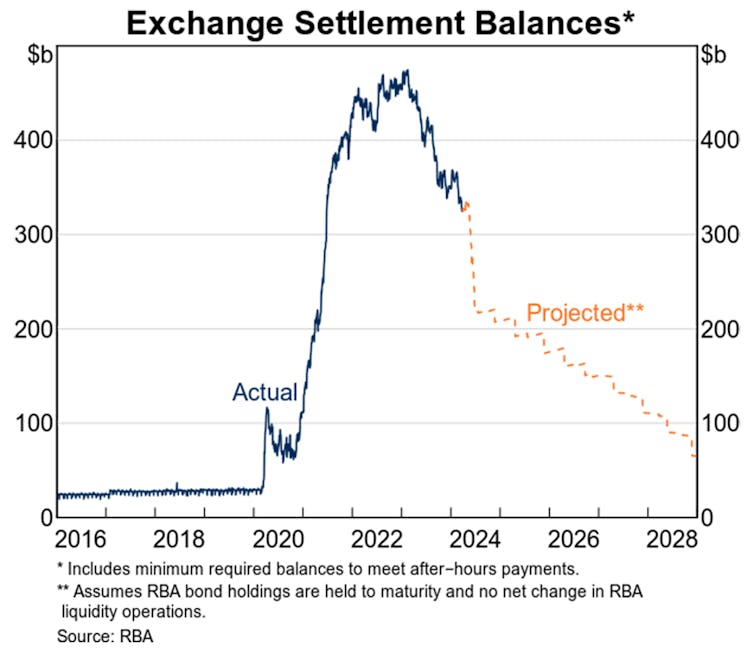

With the crisis now over and many bonds sold during the pandemic falling due[8], the total amount of cash in exchange settlement accounts has begun to fall.

In light of this, the Reserve Bank could have chosen to continue with its current (costly) abundant reserves system, or to revert back to scarce reserves.

But its board has chosen to embrace a third option that mixes the two: “ample reserves[10]”.

Under this approach, the Reserve Bank will continue to supply plenty of funds that banks can freely borrow at the target cash rate, which will ensure it still controls interest rates. But it will now also focus on limiting excess cash reserves in the financial system, to keep the cost of those interest payments down.

As the Reserve Bank navigates from a system of excess to ample reserves, careful monitoring and adjustments will be crucial, especially as it responds to market conditions and liquidity needs. The plan announced by the Reserve Bank didn’t contain any specific numbers about the size of the balance sheet, which will have to be worked out over time as the demand for reserves evolves.

The ultimate goal is to achieve a more efficient, stable, and flexible system for monetary policy implementation that supports the Australian economy while minimising central bank intervention in markets.

Reworking the plumbing of the monetary system won’t garner much mainstream attention, but plays a vital role in stabilising the economy without breaking the bank.

Read more: Rising bank profits highlight tensions between competition watchdogs and central banks[11]

References

- ^ cash rate (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ set to change again (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ more than A$200 billion daily (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ Dan Peled/AAP (photos.aap.com.au)

- ^ Interest rates are expected to drop but trying to out-think the market won't guarantee getting a good deal (theconversation.com)

- ^ Joel Carrett/AAP (photos.aap.com.au)

- ^ more than A$40 billion (www.afr.com)

- ^ falling due (www.bloomberg.com)

- ^ RBA (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ ample reserves (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ Rising bank profits highlight tensions between competition watchdogs and central banks (theconversation.com)

Authors: Isaac Gross, Lecturer in Economics, Monash University