Electric heat pumps use much less energy than furnaces, and can cool houses too – here's how they work

- Written by Robert Brecha, Professor of Sustainability, University of Dayton

To help curb climate change, President Biden has set a goal of lowering U.S. greenhouse gas emissions 50%-52% below 2005 levels by 2030[1]. Meeting this target will require rapidly converting as many fossil fuel-powered activities to electricity as possible, and then generating that electricity from low-carbon and carbon-free sources such as wind, solar, hydropower and nuclear energy.

The buildings that people live[2] and work[3] in consume substantial amounts of energy. In 2019, commercial and residential buildings accounted for more than one-seventh[4] of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. New heating and cooling strategies are an important piece of the puzzle.

Fortunately, there’s an existing technology that can do this: electric heat pumps that are three to four times more efficient than furnaces. These devices heat homes in winter and cool them in summer by moving heat in and out of buildings, rather than by burning fossil fuel.

As a scientist focusing on renewable and clean energy[5], I study energy use in housing[6] and what slowing climate change means for industrialized[7] and developing countries[8]. I see powering buildings with clean, renewable electricity as an essential strategy that also will save consumers money.

Heat pumps draw in air from the outside and use the difference in temperature between indoor and outdoor air to heat buildings. Many also provide cooling, using nearly the same mechanism.Heat pumps work by moving heat, not air

Most heating systems in the U.S. use forced-air furnaces that run on natural gas or electricity, or in some cases heating oil[9]. To heat the building, the systems burn fuel or use electricity to heat up air, and then blow the warm air through ducts into individual rooms.

A heat pump works more like a refrigerator[10], which extracts energy from the air inside the fridge and dumps that energy into the room, leaving the inside cooler. To heat a building, a heat pump extracts energy from outdoor air[11] or from the ground[12] and converts it to heat for the house.

Here’s how it works: Extremely cold fluid circulates through coils of tubing in the heat pump’s outdoor unit. That fluid absorbs energy in the form of heat from the surrounding air, which is warmer than the fluid. The fluid vaporizes and then circulates into a compressor. Compressing any gas heats it up[13], so this process generates heat. Then the vapor moves through coils of tubing in the indoor unit of the heat pump, heating the building.

In summer, the heat pump runs in reverse and takes energy from the room and moves that heat outdoors, even though it’s hotter outside – basically, functioning like a bigger version of a refrigerator.

More efficient than furnaces

Heat pumps require some electricity to run, but it’s a relatively small amount. Modern heat pump systems can transfer three or four times more thermal energy in the form of heat than they consume in electrical energy to do this work – and that the homeowner pays for.

In contrast, converting energy from one form to another, as conventional heating systems do, always wastes some of it[14]. That’s true for burning oil or gas to heat air in a furnace, or using electric heaters to heat air – although in that case, the waste occurs when the electricity is generated. About two-thirds of the energy used to produce electricity at a power plant is lost in the process[15].

Retrofitting residences[16] and commercial buildings[17] with heat pumps increases heating efficiency. When combined with a switch from fossil fuels to renewables, it further lowers energy use and carbon emissions.

Going electric

Growing restrictions on fossil fuel use[18] and proactive policies[19] are driving sales of heat pumps[20] in the U.S. and internationally. Heat pumps are currently used in 5% of heating systems worldwide, a share that will need to increase to one-third by 2030 and much higher after to reach net-zero emissions by 2050[21].

In warmer areas with relatively low heating demands, heat pumps are cheaper to run than furnaces. Tax credits, utility rebates or other subsidies may also provide incentives to help with up-front costs, including federal incentives reinstated by the Biden administration[22].

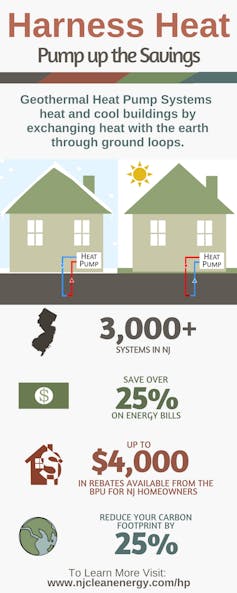

In extremely cold climates, these systems have an extra internal heater to help out. This unit is not as efficient, and can significantly run up electric bills. People who live in cold locations may want to consider geothermal heat pumps[23] as an alternative.

Geothermal heat pumps may be a better option than air-source versions in colder climates.

NJDEP[24]

Geothermal heat pumps may be a better option than air-source versions in colder climates.

NJDEP[24]

These systems leverage the fact that ground temperature is warmer than the air in winter. Geothermal systems collect warmth from the earth and use the same fluid and compressor technology as air source heat pumps to transfer heat into buildings. They cost more, since installing them involves excavation to bury tubing below ground, but they also reduce electricity use[25].

New, smaller “mini-split” heat pump systems[26] work well in all but the coldest climates. Instead of requiring ducts to move air through buildings, these systems connect to wall-mounted units that heat or cool individual rooms. They are easy to install and can be selectively used in individual apartments, which makes retrofitting large buildings easier.

Even with the best heating and cooling systems, installing proper insulation and sealing building leaks[27] are key to reducing energy use. You can also experiment with your thermostat to see how little you can heat or cool your home while keeping everyone in it comfortable.

A new mini split heat pump system.

Robert Brecha, CC BY-ND[28]

A new mini split heat pump system.

Robert Brecha, CC BY-ND[28]

For help figuring out whether a heat pump can work for you, one good source of information is your electricity provider. Many utilities offer home energy audits that can identify cost-effective ways to make your home more energy-efficient. Other good sources include the U.S. Department of Energy[29] and the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy[30]. As the push to electrify society gains speed, heat pumps are ready to play a central role.

[The Conversation’s science, health and technology editors pick their favorite stories. Weekly on Wednesdays[31].]

References

- ^ 50%-52% below 2005 levels by 2030 (www.whitehouse.gov)

- ^ live (www.eia.gov)

- ^ work (www.eia.gov)

- ^ more than one-seventh (www.epa.gov)

- ^ renewable and clean energy (scholar.google.de)

- ^ energy use in housing (doi.org)

- ^ industrialized (climateanalytics.org)

- ^ developing countries (climateanalytics.org)

- ^ heating oil (www.eia.gov)

- ^ works more like a refrigerator (www.brighthubengineering.com)

- ^ outdoor air (www.energy.gov)

- ^ from the ground (www.energy.gov)

- ^ Compressing any gas heats it up (www.youtube.com)

- ^ always wastes some of it (www.livescience.com)

- ^ lost in the process (www.eia.gov)

- ^ residences (www.aceee.org)

- ^ commercial buildings (www.aceee.org)

- ^ restrictions on fossil fuel use (www.eenews.net)

- ^ proactive policies (www.aceee.org)

- ^ driving sales of heat pumps (www.iea.org)

- ^ net-zero emissions by 2050 (www.iea.org)

- ^ reinstated by the Biden administration (www.energystar.gov)

- ^ geothermal heat pumps (www.energy.gov)

- ^ NJDEP (www.nj.gov)

- ^ reduce electricity use (www.energy.gov)

- ^ mini-split” heat pump systems (www.energy.gov)

- ^ installing proper insulation and sealing building leaks (www.energystar.gov)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ U.S. Department of Energy (www.energy.gov)

- ^ American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (www.aceee.org)

- ^ Weekly on Wednesdays (theconversation.com)