the hidden cost of psychopaths at work

- Written by Benedict Sheehy, Associate professor, University of Canberra

From psychological thrillers to true crime stories, people who depart from social norms can be deeply fascinating. Psychopaths most of all.

Working with or for a psychopath, however, is less fun.

The research generally agrees about 1% of the population is psychopathic. This means they fail to develop the normal range of emotions, lack empathy for others and are more disposed to antisocial and uninhibited behaviour.

Among prisoners, the percentage with psychopathic traits has been estimated at 15%[1] to 20%. But psychopaths are also disproportionately represented in corporate culture. Among the higher echelons of large organisations, the psychopathy rate is an estimated 3.5%[2]. Some estimates for chief executives go way higher.

Only in recent decades has the research on psychopathy started reflecting the enormity of the social and economic cost of non-criminal corporate psychopaths. My research (with Clive Boddy and Brendon Murphy[3]) suggests corporate psychopaths cost the economy billions of dollars not only through fraud and other crimes but through the personal and organisational damage they leave behind as they climb the corporate ladder.

Read more: What is a psychopath?[4]

Worming their way in

Psychopaths typically lack empathy and remorse. They are self-centred, manipulative, unemotional, deceitful, insincere and self-aggrandising.

But they are also fearless and confident, which helps them present as potentially resourceful employees and gain employment.

Read more: Pathological power: the danger of governments led by narcissists and psychopaths[5]

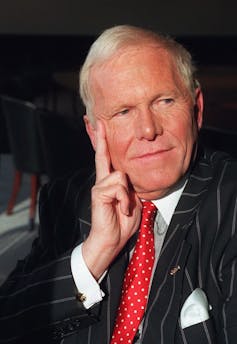

Al Dunlap in March 1998, when chairman and chief executive of Sunbeam Corp. He was fired in June that year when it emerged he had fraudulently made the appliance maker look more profitable.

Adam Nadel/AP

Al Dunlap in March 1998, when chairman and chief executive of Sunbeam Corp. He was fired in June that year when it emerged he had fraudulently made the appliance maker look more profitable.

Adam Nadel/AP

A classic example is “Chainsaw Al” Dunlap, who in the early 1990s was celebrated as a hard-nosed but effective corporate “streamliner”, turning around company fortunes by retrenching staff. Dunlap has been identified as holding strong psychopathic traits[6]. It turned out, though, that his success had more to do with his willingness to commit fraud than his lack of compassion.

In reality, it’s hard to conceive of any situation where an organisation would benefit from recruiting someone with psychopathic tendencies. Once in position, their combination of traits will often lead them to engage in unethical and exploitative behaviour, disregarding the norms that allow people to work together harmoniously.

In his 2017 book A Climate of Fear: Stone Cold Psychopaths at Work[7], Clive Boddy describes how corporate psychopaths:

- use organisational restructures to weaken potential threats

- bully colleagues into obedience

- spread rumours to undermine competitors

- deploy “upward impression management techniques” to project competence

- justify poor behaviour as “hard decisions that had to be made”.

The corporate psychopath damages the organisation through actions designed to promote their own psychological needs.

Andrii Yalanskyi/Shutterstock

The corporate psychopath damages the organisation through actions designed to promote their own psychological needs.

Andrii Yalanskyi/Shutterstock

Read more: The preferred jobs of serial killers and psychopaths[8]

What the law says

Being a psychopath isn’t illegal. The only area where the law intervenes on the basis of a psychological diagnosis is when mental illness is seen to endanger the safety of the subject or others. Psychopathy is a personality disorder, not a mental illness. There’s no legal remedy for psychopathic behaviours that don’t rise to the level of a firing offence – such as fraud, theft or sexual harassment.

In some cases, it may be possible to minimise the damage a psychopath can do through taking a harder line on behavioural standards. Bullying and harassment are overt warning signs of other behaviour toxic to the work culture. A record of such behaviour should be a strike against having power over other employees.

Truth is the best defence

The first and main line of defence against corporate psychopaths has to be prevention.

There’s no surefire way to avoid recruiting a psychopath but key to reducing the risk is “sceptical due diligence” – checking the claims a job applicant makes.

Psychopaths have a natural advantage in any superficial recruitment process due their lower inhibition against claiming qualifications[9], experience and competencies they don’t have, and for taking credit for work they didn’t do.

It therefore pays to verify a candidate’s claimed qualifications, to scrutinise all their verbal and written claims, and test them on their honesty, truthfulness and capacity to give credit where it is due. They might have a glowing reference from a past manager, but what about other colleagues? Someone in a junior role to the recruit under consideration is more likely than a past manager to have seen the person’s true character.

Asking the hard questions prior to hiring arguably becomes more important the more senior the role. In a range of contexts we are increasingly recognising the consequences of failing to take complaints seriously. Smoke doesn’t necessarily mean fire, but when an individual is found responsible for one fire, it is likely they have started others.

Read more: Narcissists and psychopaths: how some societies ensure these dangerous people never wield power[10]

The corporate psychopath is a fascinating but dangerous character. As we come to appreciate how much damage they can do, it’s not a character you should want to study close up.

References

- ^ 15% (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ an estimated 3.5% (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ Clive Boddy and Brendon Murphy (papers.ssrn.com)

- ^ What is a psychopath? (theconversation.com)

- ^ Pathological power: the danger of governments led by narcissists and psychopaths (theconversation.com)

- ^ strong psychopathic traits (eprints.utas.edu.au)

- ^ A Climate of Fear: Stone Cold Psychopaths at Work (books.google.com.au)

- ^ The preferred jobs of serial killers and psychopaths (theconversation.com)

- ^ claiming qualifications (eprints.mdx.ac.uk)

- ^ Narcissists and psychopaths: how some societies ensure these dangerous people never wield power (theconversation.com)

Authors: Benedict Sheehy, Associate professor, University of Canberra

Read more https://theconversation.com/bullies-thieves-and-chiefs-the-hidden-cost-of-psychopaths-at-work-149152