Sure, the US election is gerrymandered, but so are others, and its hard to stop

- Written by Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

At the time of writing we don’t yet know who will win the US presidential election.

But we do know this for sure: Donald Trump will be able to win with less than half the votes cast. Put another way, Joe Biden will be able to lose even if he wins the popular vote.

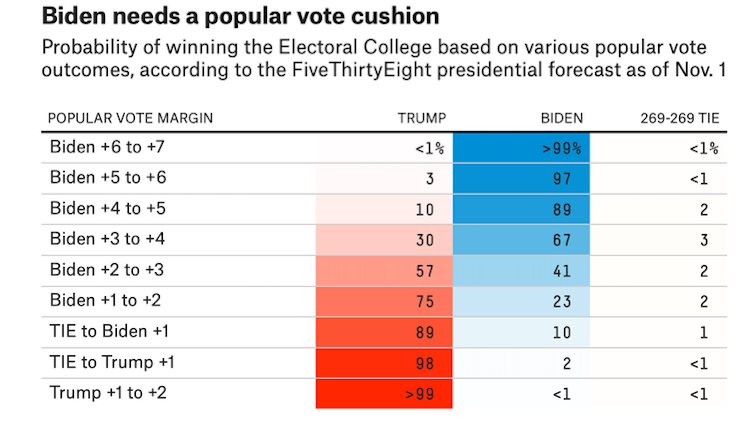

Election analyst Nate Silver believes Biden would have to win by three to four percentage points to have a better than 50% chance of winning the presidency.

fivethirthyeight.com The same was true in 2016. Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by around two percentage points but lost the presidency. And in 2000. Al Gore won the popular vote but lost the presidency. Part of the reason is the geographically-based US electoral college system in which voters don’t directly elect the president but elect representatives who will vote on their behalf in an electoral college[1]. But another part is the result of a more general problem called gerrymandering[2].

fivethirthyeight.com The same was true in 2016. Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by around two percentage points but lost the presidency. And in 2000. Al Gore won the popular vote but lost the presidency. Part of the reason is the geographically-based US electoral college system in which voters don’t directly elect the president but elect representatives who will vote on their behalf in an electoral college[1]. But another part is the result of a more general problem called gerrymandering[2].  Elbridge Gerry’s salamander. Brittanica.com The term is named after a governor of Massachusetts Elbridge Gerry who, in 1812, drew a district (with a pencil, on a map, on the floor of the study in his house in Cambridge MA) so oddly shaped that political cartoonists said it resembled a salamander. They christened his plan a “gerrymander[3]”. Oddly shaped electorates can be designed to combine voters in very specific ways, limiting an opposing party’s ability to win many electorates. The 4th Congressional district in Illinois, in the United States, is a famous example – combining votes from the North and South sides of Chicago, and running along a freeway at one point.

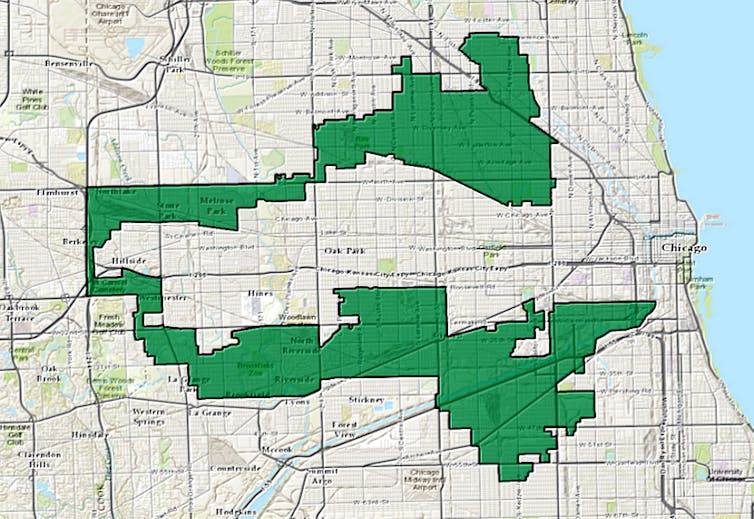

Elbridge Gerry’s salamander. Brittanica.com The term is named after a governor of Massachusetts Elbridge Gerry who, in 1812, drew a district (with a pencil, on a map, on the floor of the study in his house in Cambridge MA) so oddly shaped that political cartoonists said it resembled a salamander. They christened his plan a “gerrymander[3]”. Oddly shaped electorates can be designed to combine voters in very specific ways, limiting an opposing party’s ability to win many electorates. The 4th Congressional district in Illinois, in the United States, is a famous example – combining votes from the North and South sides of Chicago, and running along a freeway at one point.  Illinois 4th Congressional District. Wikipedia Even without odd shapes, where ever there is a geographic allocation of voters to electoral districts or states (as in the UK, Australia and many other countries) there is the prospect – indeed likelihood – that the popular vote won’t coincide with the winner of the majority of seats or states. It’s possible to lose lots of seats by big margins and to still come out on top by winning slightly more by narrow margins. Read more: More Americans are suing over gerrymandered state maps – but the Supreme Court is not likely to step in[4] At least in Australia and the United Kingdom, districts aren’t drawn by politicians, but in many states they are in the US. While this doesn’t matter much for presidential elections, it has led people like me to spend a fair amount of time devoted to seeking to understand the motives[5] of gerrymanders, whether they have advantaged incumbents[6], how to draw geographically-sensible[7] looking districts, and how to use automatic means[8] to change district boundaries as populations change. One problem in the US is that even if the rules don’t change, voters naturally move between districts, often congregating with like-minded people, creating the effect of a gerrymander. Read more: 4 reasons gerrymandering is getting worse[9] Even an independent electoral commission[10], such as Australia’s will find it hard to ensure that the party that wins the majority vote will be the party that takes office. And they are not required to[11]. For federal elections the redistribution commissioners are required only to ensure that the number of voters in each electorate is roughly the same as in other electorates within the state. In doing it they are required to take account of communities of interests, means of travel, and physical features. To look at the distribution of each party’s supporters and ensure it was evenly spread between electorates would be a highly political act. It would involve making political judgements. South Australia’s Electoral Districts Boundaries Commission[12] was required to make those judgements between 1991 and 2016. During those years it was told to ensure as far as practicable, that the redistribution was fair to prospective candidates and groups of candidates, so that if candidates of a particular group attracted more than 50 per cent of the popular vote, including preferences, they would be elected in sufficient numbers to enable a government to be formed. Until the law was repealed amid accusations about which side of politics would benefit[13] South Australia was the only Australian state in which authorities were required to give consideration to political outcomes when drawing up electorates. We are told that it no longer happens in South Australia and happens nowhere else in Australia. And it doesn’t, explicitly. Read more: Explainer: how do seat redistributions work?[14] Yet implicitly redistribution commissions do make those calls making judgements that will either advance majority rule or retard it, regardless of whether they say or think they are. It’s something that as voters and citizens, we should be aware of.

Illinois 4th Congressional District. Wikipedia Even without odd shapes, where ever there is a geographic allocation of voters to electoral districts or states (as in the UK, Australia and many other countries) there is the prospect – indeed likelihood – that the popular vote won’t coincide with the winner of the majority of seats or states. It’s possible to lose lots of seats by big margins and to still come out on top by winning slightly more by narrow margins. Read more: More Americans are suing over gerrymandered state maps – but the Supreme Court is not likely to step in[4] At least in Australia and the United Kingdom, districts aren’t drawn by politicians, but in many states they are in the US. While this doesn’t matter much for presidential elections, it has led people like me to spend a fair amount of time devoted to seeking to understand the motives[5] of gerrymanders, whether they have advantaged incumbents[6], how to draw geographically-sensible[7] looking districts, and how to use automatic means[8] to change district boundaries as populations change. One problem in the US is that even if the rules don’t change, voters naturally move between districts, often congregating with like-minded people, creating the effect of a gerrymander. Read more: 4 reasons gerrymandering is getting worse[9] Even an independent electoral commission[10], such as Australia’s will find it hard to ensure that the party that wins the majority vote will be the party that takes office. And they are not required to[11]. For federal elections the redistribution commissioners are required only to ensure that the number of voters in each electorate is roughly the same as in other electorates within the state. In doing it they are required to take account of communities of interests, means of travel, and physical features. To look at the distribution of each party’s supporters and ensure it was evenly spread between electorates would be a highly political act. It would involve making political judgements. South Australia’s Electoral Districts Boundaries Commission[12] was required to make those judgements between 1991 and 2016. During those years it was told to ensure as far as practicable, that the redistribution was fair to prospective candidates and groups of candidates, so that if candidates of a particular group attracted more than 50 per cent of the popular vote, including preferences, they would be elected in sufficient numbers to enable a government to be formed. Until the law was repealed amid accusations about which side of politics would benefit[13] South Australia was the only Australian state in which authorities were required to give consideration to political outcomes when drawing up electorates. We are told that it no longer happens in South Australia and happens nowhere else in Australia. And it doesn’t, explicitly. Read more: Explainer: how do seat redistributions work?[14] Yet implicitly redistribution commissions do make those calls making judgements that will either advance majority rule or retard it, regardless of whether they say or think they are. It’s something that as voters and citizens, we should be aware of. References

- ^ electoral college (au.news.yahoo.com)

- ^ gerrymandering (www.britannica.com)

- ^ gerrymander (fivethirtyeight.com)

- ^ More Americans are suing over gerrymandered state maps – but the Supreme Court is not likely to step in (theconversation.com)

- ^ motives (research.economics.unsw.edu.au)

- ^ advantaged incumbents (research.economics.unsw.edu.au)

- ^ geographically-sensible (research.economics.unsw.edu.au)

- ^ automatic means (research.economics.unsw.edu.au)

- ^ 4 reasons gerrymandering is getting worse (theconversation.com)

- ^ electoral commission (www.aec.gov.au)

- ^ not required to (www.aph.gov.au)

- ^ Electoral Districts Boundaries Commission (edbc.sa.gov.au)

- ^ which side of politics would benefit (www.themercury.com.au)

- ^ Explainer: how do seat redistributions work? (theconversation.com)

Authors: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW