50 years ago Milton Friedman told us greed was good. He was half right

- Written by Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

The point is, ladies and gentleman, that greed – for lack of a better word – is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms – greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge – has marked the upward surge of mankind.

– Gordon Gekko, Wall Street[1] 1987

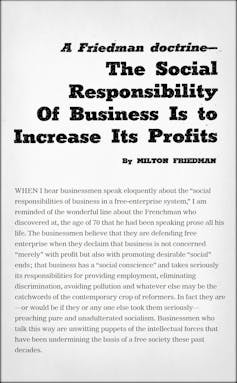

Fifty years ago, well before the movie Wall Street, Chicago economist Milton Friedman set down what for many was the essence of the famous speech in Wall Street in an article for the New York times magazine entitled “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits[2]”.

His point, which along with his other contributions was recognised when he was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences[3] in 1976, was that businesses serve society best when they abandon talk of “social responsibilities” and solely maximise returns for shareholders.

Incredibly influential (the past week has seen special conferences[4] and anniversary analyses[5]), the essay has been credited with ushering in the doctrine of “shareholder primacy[6],” and with it short-termism, hostile takeovers, colossal frauds[7] and savage job cuts.

Its a doctrine not seriously challenged until the 2008-2009 global financial crisis.

The essay that sparked a revolution, 50 years ago this week.

New York Times[8]

The essay that sparked a revolution, 50 years ago this week.

New York Times[8]

But in an important respect it was misread.

Although not clear from the title of the essay[9], Friedman himself was quite concerned with broader social aims.

His essay was about how best to achieve them.

His point was that if companies made as much money as they could for their shareholders, those shareholders could spend it on social goals, “if they wished to do so”.

For the company to attempt to guess what goals its shareholders would want to support and to support them itself would be for the company to do its main job badly.

Although it made a certain sort of sense, the Friedman doctrine has turned out to be incomplete.

As Harvard University’s Oliver Hart (who also won the Nobel Prize for Economics) has points out, corporations are often much better[10] than their shareholders at achieving the goals their shareholders care about.

Corporations can achieve more than individuals

Individual shareholders can’t do much to avert climate change, but the corporations they own can.

A mining company could either stop operating an environmentally-damaging mine or run the mine, make a bunch of money and pay it to shareholders who could use the money to mitigate the damage “if they wished to do so”.

Its hard to argue that, if shareholders do indeed “wish to do so”, the first option isn’t better.

To cite a recent instance, is hard to “un-blow-up” 46,000 years of Indigenous heritage[11].

Read more: Corporate dysfunction on Indigenous affairs: Why heads rolled at Rio Tinto[12]

In contrast, Friedman was almost surely right about corporate charitable contributions, which was in many ways the impetus for the article.

In what way are corporations better at giving money to charities (and political parties) than individuals. In none that are obvious (and not potentially corrupt).

So where do we draw the line about what corporations do and don’t do?

Proponents of the “stakeholder view” now endorsed by an increasing number of superannuation funds[13] think corporations should have a composite objective that takes into account the interests of shareholders, bondholders, workers, suppliers, the environment, and more.

Yet a point in every direction…

The problem with this, as recognised by the arrow-covered pointless man in the animated Harry Nilsson film What’s The Point?[14] is that “a point in every direction is the same as no point at all”.

As Friedman put it, composite objectives suffer from “looseness and lack of rigour”.

Others, such as Hart and University of Chicago professor Luigi Zingales think firms should find out what shareholders most want, and “pursue that goal[15].”

This has the virtue of permitting a social objective while creating a concrete, measurable goal.

It’s a way of giving shareholders (and super fund members) a voice that is more direct than simply electing directors every few years.

Friedman helped start an important discussion. Fifty years on, it isn’t finished.

References

- ^ Wall Street (www.americanrhetoric.com)

- ^ The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (www.nobelprize.org)

- ^ special conferences (fund-shack.com)

- ^ anniversary analyses (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ shareholder primacy (corporatefinanceinstitute.com)

- ^ colossal frauds (www.investopedia.com)

- ^ New York Times (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ title of the essay (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ much better (promarket.org)

- ^ 46,000 years of Indigenous heritage (theconversation.com)

- ^ Corporate dysfunction on Indigenous affairs: Why heads rolled at Rio Tinto (theconversation.com)

- ^ increasing number of superannuation funds (theconversation.com)

- ^ What’s The Point? (brightlightsfilm.com)

- ^ pursue that goal (promarket.org)

Authors: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW