An extra $1.7 billion for child care will help some. It won't improve affordability for most

- Written by Kate Noble, Education Policy Fellow, Mitchell Institute, Victoria University

The Australian government has announced big changes[1] to its child-care subsidy ahead of the May 11 federal budget.

The changes involve adding A$1.7 billion to the A$10.3 billion a year already budgeted for child care. This spending will particularly benefit families with two or more children under five. It will also help couples with a combined income of more than A$189,390, by removing the subsidy cap[2] that restricts them to a maximum of A$10,560 per child a year.

The government says[3] the changes “deliberately target low and middle income earners, with around half the families set to benefit having a household income under $130,000”.

How will these changes affect you? In the short term, not at all. They won’t affect anyone until July 2022. After that some families will see great benefit.

But our analysis suggests the policy package won’t do much to improve the affordability of child care for many families on low to middle incomes. Nor will it do anything to address systemic problems.

Read more: The child-care sector needs an overhaul, not more tinkering with subsidies and tax deductions[4]

Defining affordability

A lot of the discussion on child-care affordability focuses on per-hour costs[5] and anecdotal evidence based on individual families’ circumstances.

Families’ lived experiences are important, as are average out-of-pocket fees. But without understanding what affordability means, it’s very difficult to pin down how much of an issue child-care affordability actually is.

Australia has tackled the question of affordability in relation to housing and energy[6] costs. Housing stress for lower-income households, for example, is defined as a lower-income household spending a more than 30% of gross income on accommodation[7].

In Australia, we don’t have a comparable threshold for child-care affordability.

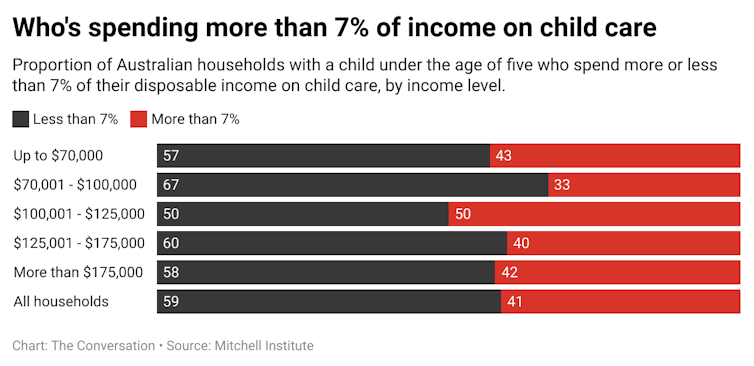

The US Department of Health and Human Services has set an “affordability threshold[8]” for low to middle income families of 7% of take-home income. If they’re spending more than 7%, child care is considered “unaffordable”.

How these measures affect affordability

Increasing subsidies for families with two children under five in child care will make a big difference to families in that situation. But child care will remain unaffordable for many.

The government has stated this package will help 250,000 families[9]. However, there are almost 1 million families[10] using child care, so the majority are unlikely to benefit from these changes.

Our analysis suggests 41% of families with one child aged under five years will continue to spend more than 7% of their disposable income on child care.

CC BY-SA[11]

That includes half of all households with annual disposable income between A$100,001 and A$125,000.

For example, a family with a combined gross annual income of A$102,000 will still face out-of-pocket costs for full-time child care of about A$11,000 a year.

So although the measures aim to make child care more affordable for those families “who really need it most[12]”, our analysis suggests child care will remain unaffordable for hundreds of thousands of Australian families.

Nor will it make child-care funding and subsidies any less complicated, despite recent reforms aimed at simplifying the system.

CC BY-SA[11]

That includes half of all households with annual disposable income between A$100,001 and A$125,000.

For example, a family with a combined gross annual income of A$102,000 will still face out-of-pocket costs for full-time child care of about A$11,000 a year.

So although the measures aim to make child care more affordable for those families “who really need it most[12]”, our analysis suggests child care will remain unaffordable for hundreds of thousands of Australian families.

Nor will it make child-care funding and subsidies any less complicated, despite recent reforms aimed at simplifying the system.

Marise Payne, the federal minister for women (and foreign minister), plays with props at the government’s child-care media announcement at Narrabundah Cottage Childcare Centre, Canberra, on Sunday May 2 2021.

Lukas Coch/AAP

What about preschool?

One issue not yet clear is how the changes will interact with other parts of the early childhood education and care system.

A child going to preschool, for example, is eligible for a different set of subsidies. Significant increases to child care subsidies could see families withdraw children from dedicated preschools and use cheaper child care services instead.

Given preschools tend to achieve higher quality ratings[13], and are important in supporting children’s transition to school, this would be a very perverse outcome.

Read more:

Families in eastern states pay around twice as much for preschool than the rest of Australia[14]

What else needs to happen?

The focus on economic growth and female workforce participation also comes at the expense of greater focus on providing a quality service for children and a decent career path for early childhood educators[15].

These changes are intended to increase demand for child care. Scaling up the sector to meet that demand, however, will present the same challenges that come with scaling up any service. There are risks of compromised quality – which is crucially important[16] in an area that so intimately affects children’s health, well-being and development.

So while these changes will be welcomed by many, the more complex issues remain, with no real indication as yet of any plan to address them.

Marise Payne, the federal minister for women (and foreign minister), plays with props at the government’s child-care media announcement at Narrabundah Cottage Childcare Centre, Canberra, on Sunday May 2 2021.

Lukas Coch/AAP

What about preschool?

One issue not yet clear is how the changes will interact with other parts of the early childhood education and care system.

A child going to preschool, for example, is eligible for a different set of subsidies. Significant increases to child care subsidies could see families withdraw children from dedicated preschools and use cheaper child care services instead.

Given preschools tend to achieve higher quality ratings[13], and are important in supporting children’s transition to school, this would be a very perverse outcome.

Read more:

Families in eastern states pay around twice as much for preschool than the rest of Australia[14]

What else needs to happen?

The focus on economic growth and female workforce participation also comes at the expense of greater focus on providing a quality service for children and a decent career path for early childhood educators[15].

These changes are intended to increase demand for child care. Scaling up the sector to meet that demand, however, will present the same challenges that come with scaling up any service. There are risks of compromised quality – which is crucially important[16] in an area that so intimately affects children’s health, well-being and development.

So while these changes will be welcomed by many, the more complex issues remain, with no real indication as yet of any plan to address them.

References

- ^ big changes (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ removing the subsidy cap (www.servicesaustralia.gov.au)

- ^ government says (joshfrydenberg.com.au)

- ^ The child-care sector needs an overhaul, not more tinkering with subsidies and tax deductions (theconversation.com)

- ^ per-hour costs (www.pc.gov.au)

- ^ energy (www.aer.gov.au)

- ^ on accommodation (www.aihw.gov.au)

- ^ affordability threshold (www.brookings.edu)

- ^ help 250,000 families (ministers.treasury.gov.au)

- ^ 1 million families (www.dese.gov.au)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ who really need it most (joshfrydenberg.com.au)

- ^ tend to achieve higher quality ratings (www.acecqa.gov.au)

- ^ Families in eastern states pay around twice as much for preschool than the rest of Australia (theconversation.com)

- ^ for early childhood educators (theconversation.com)

- ^ crucially important (colab.telethonkids.org.au)

Authors: Kate Noble, Education Policy Fellow, Mitchell Institute, Victoria University